A fund’s alpha – returns over a benchmark – is often quoted and widely misunderstood. The root of the misunderstanding comes from investors assuming that alpha is a constant – which it is not – and the funds using benchmarks that the investors cannot actually invest in. Even if an investor decides to go “passive,” there is still an active choice that needs to be made regarding the basket of ETFs he needs to invest in. Let’s answer the first question: What exactly is the active manager’s value add?

Alpha over a basket of ETFs

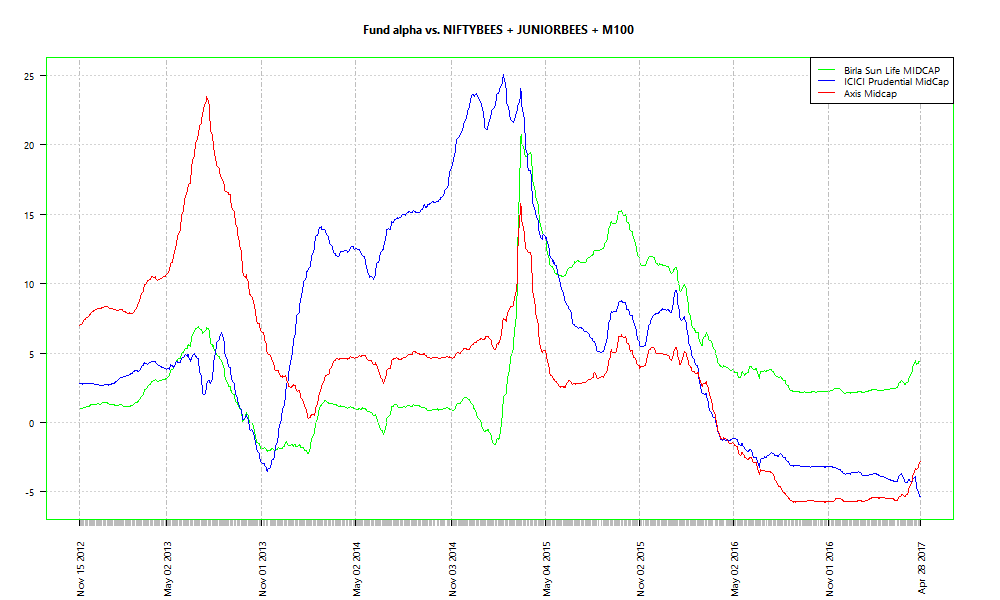

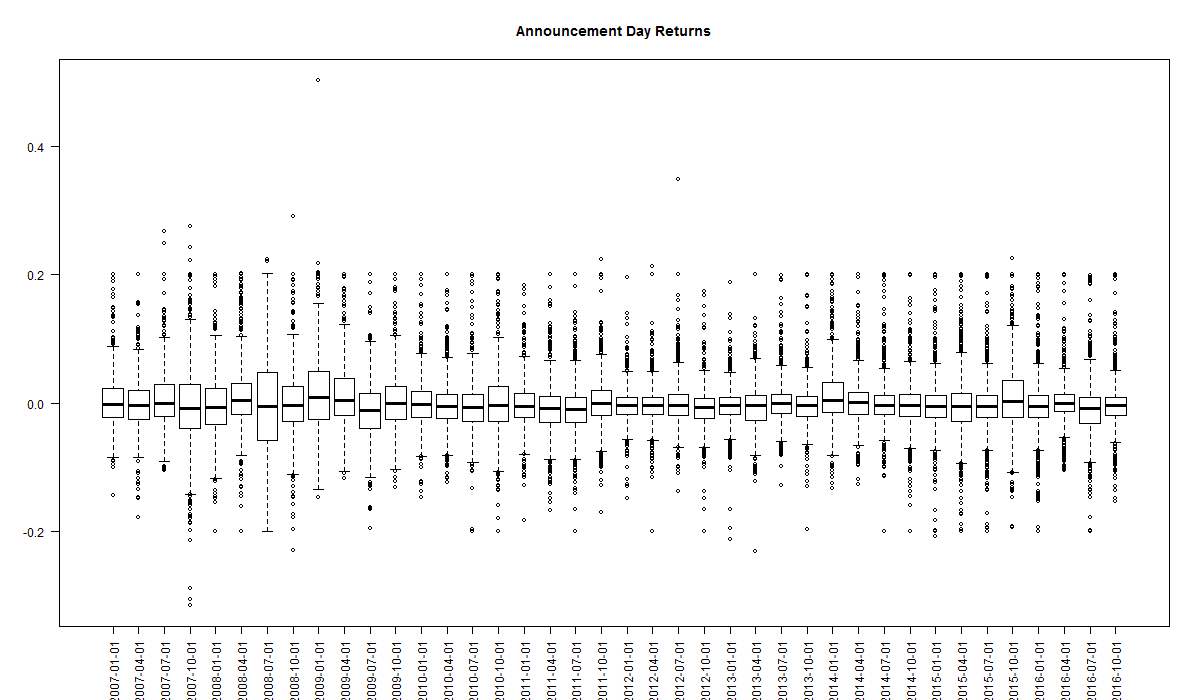

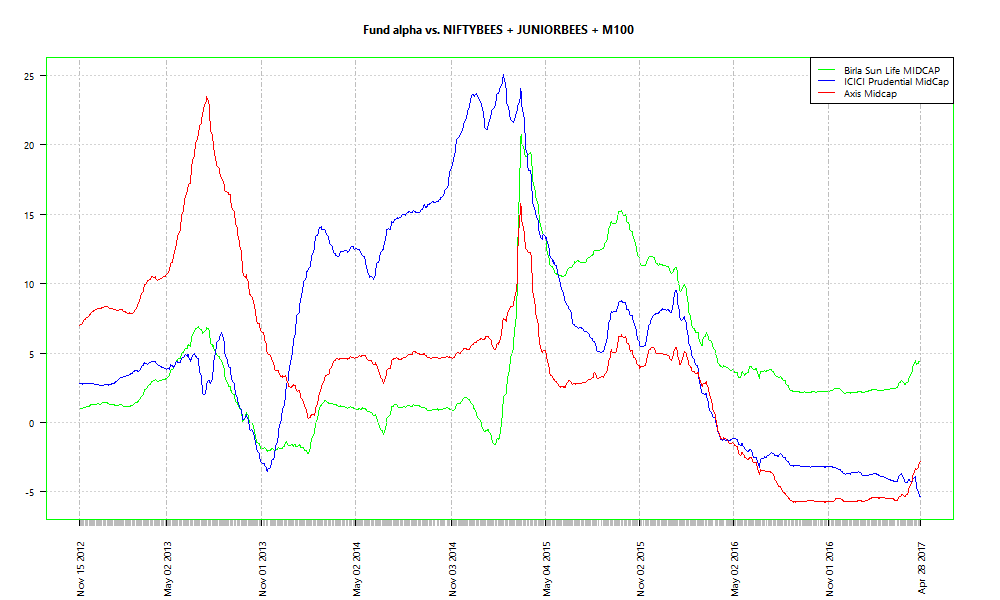

We select three ETFs, NIFTYBEES, JUNIORBEES and M100, since they are popular and span a fairly decent spectrum of traded stocks in the market. Then, we do a rolling (window of 200) linear regression of returns over 200 days of a few midcap funds (selected at random.) The intercept is the alpha of the fund vs. the ETFs. Here’s how the alpha varies over a period of time:

Two out of the three funds have negative alpha over the ETF basket right now. However, that doesn’t mean that they will stay there.

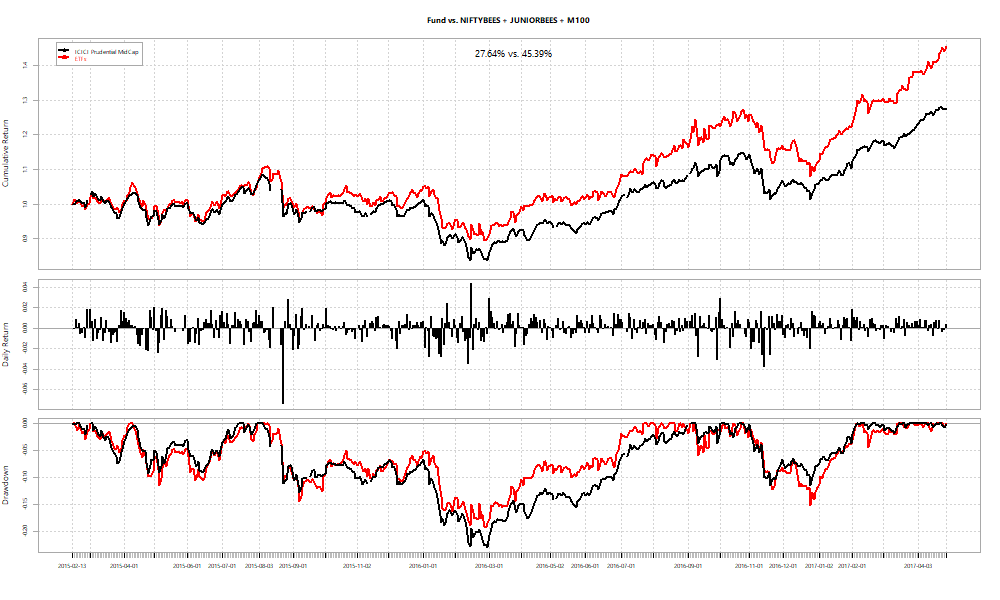

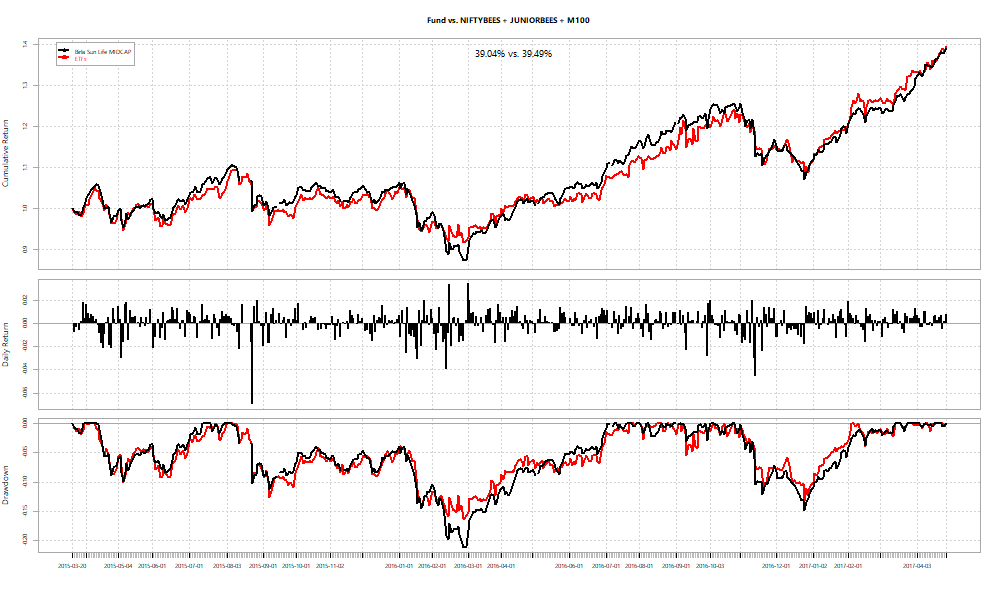

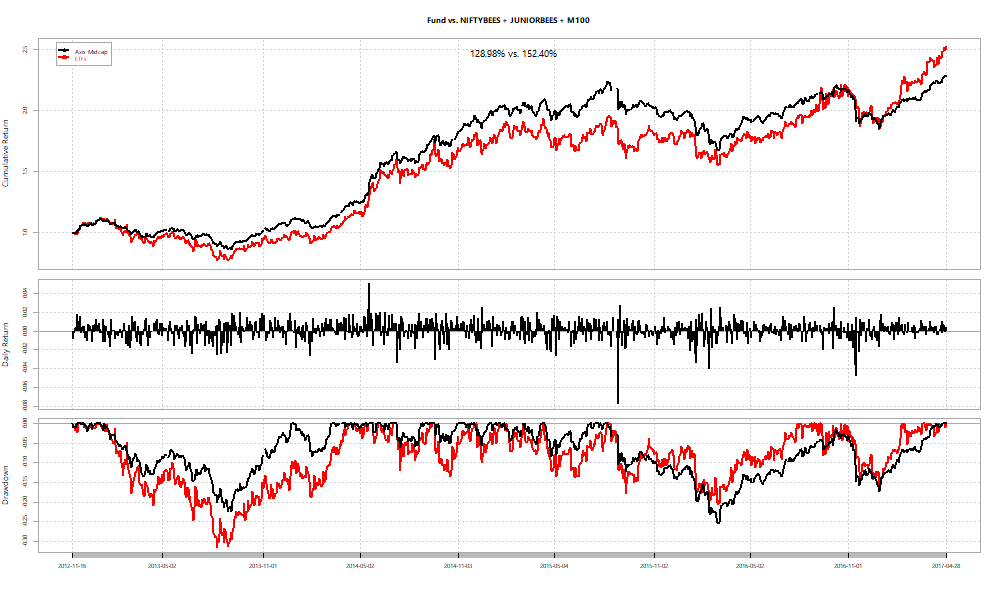

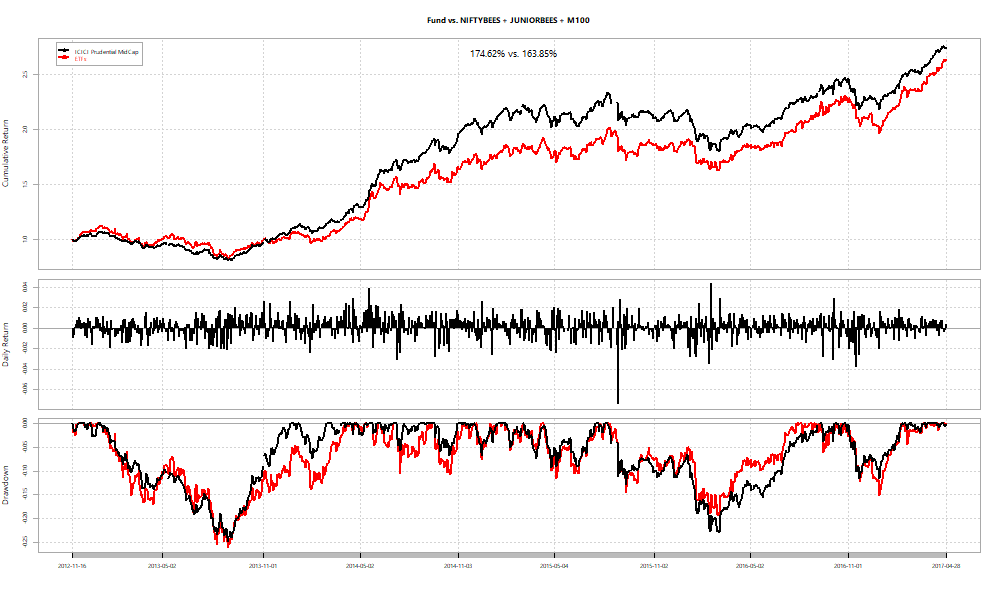

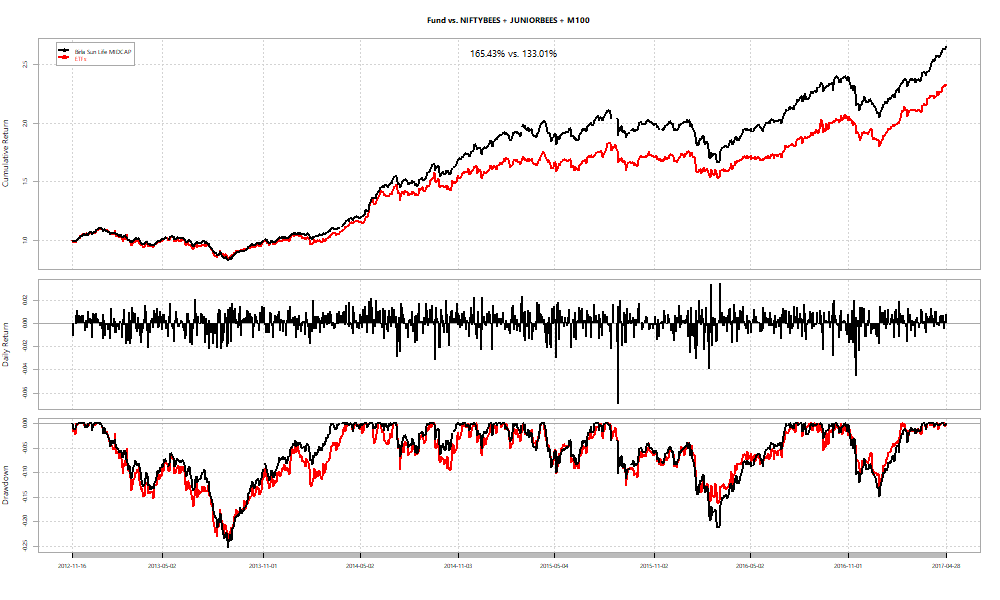

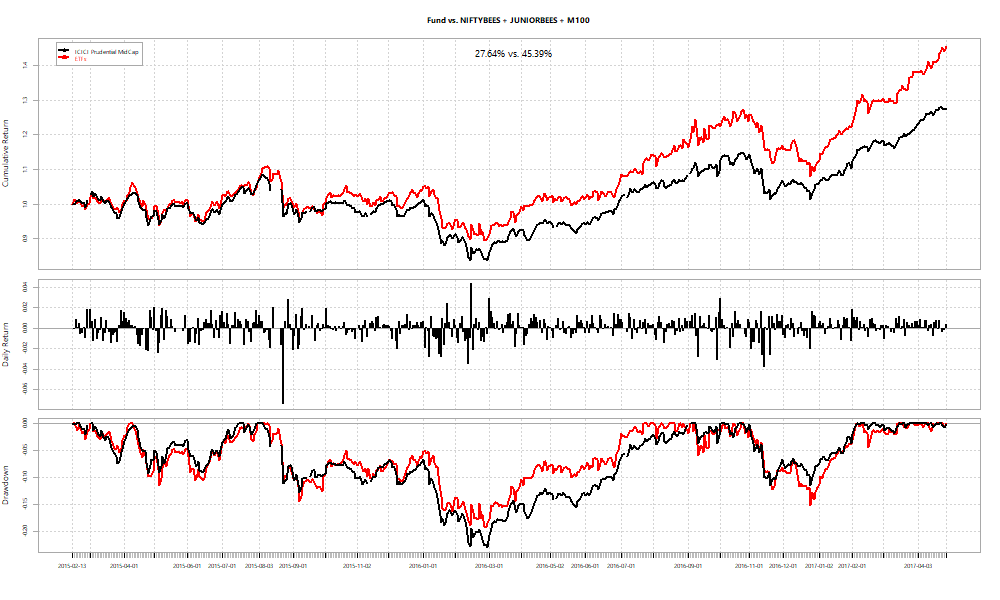

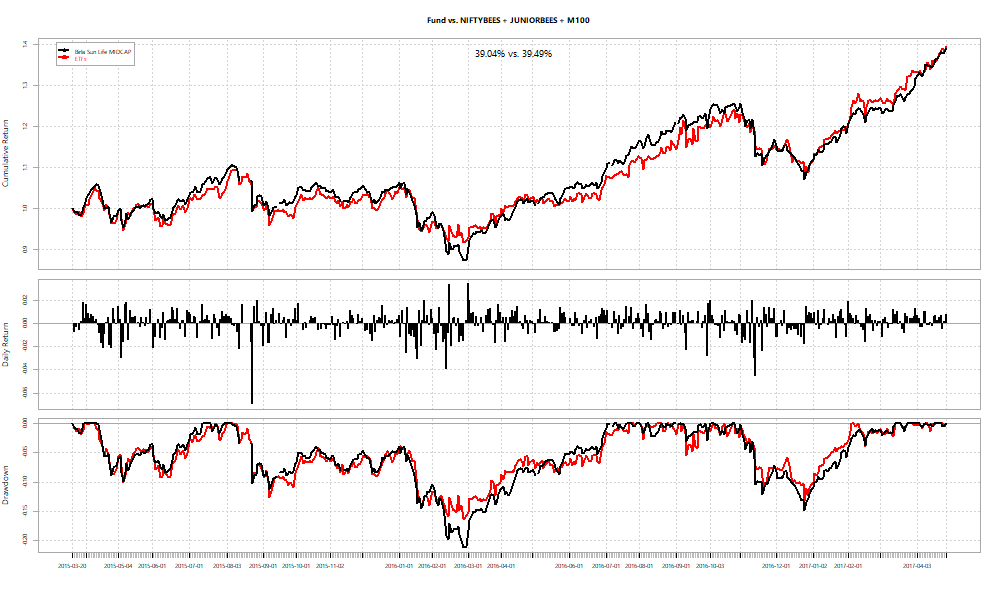

As an investor, you can use the betas obtained by the regression over the ETFs to “replicate” the fund at a point in time. For example, if you set the start date as the date at which each of the funds had peak alpha and just held onto the basket, here’s how the relative performances look:

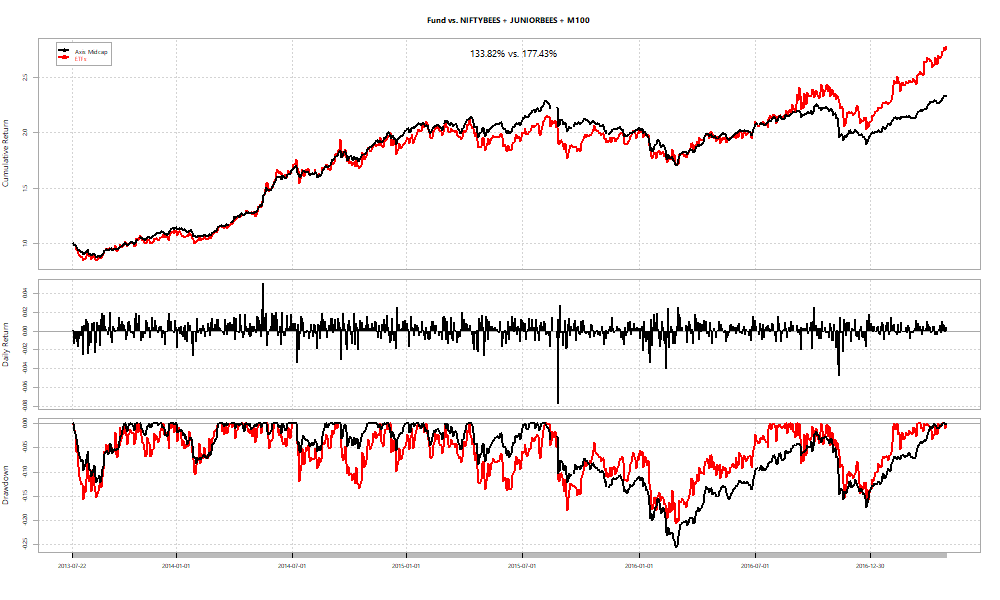

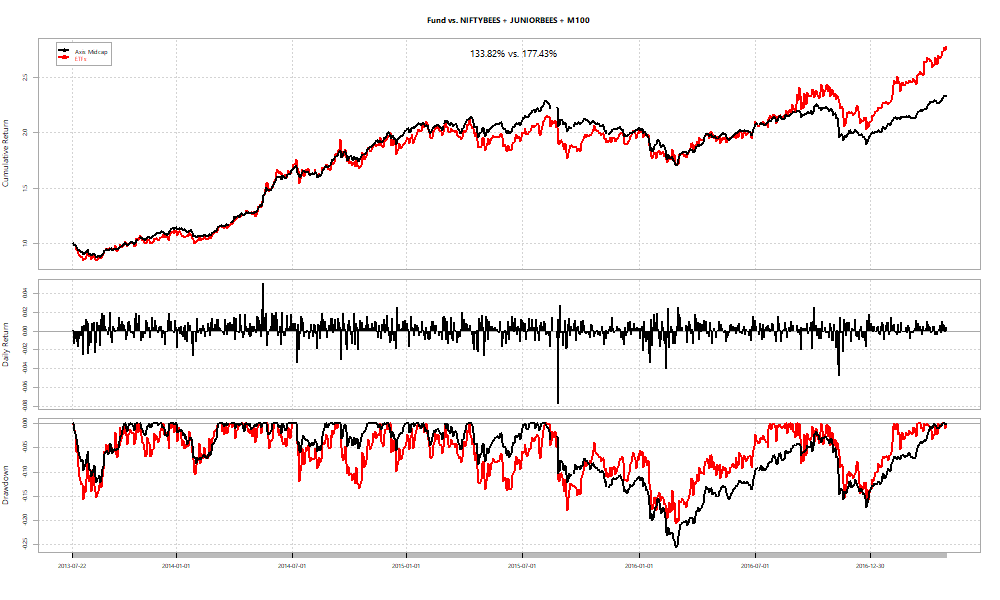

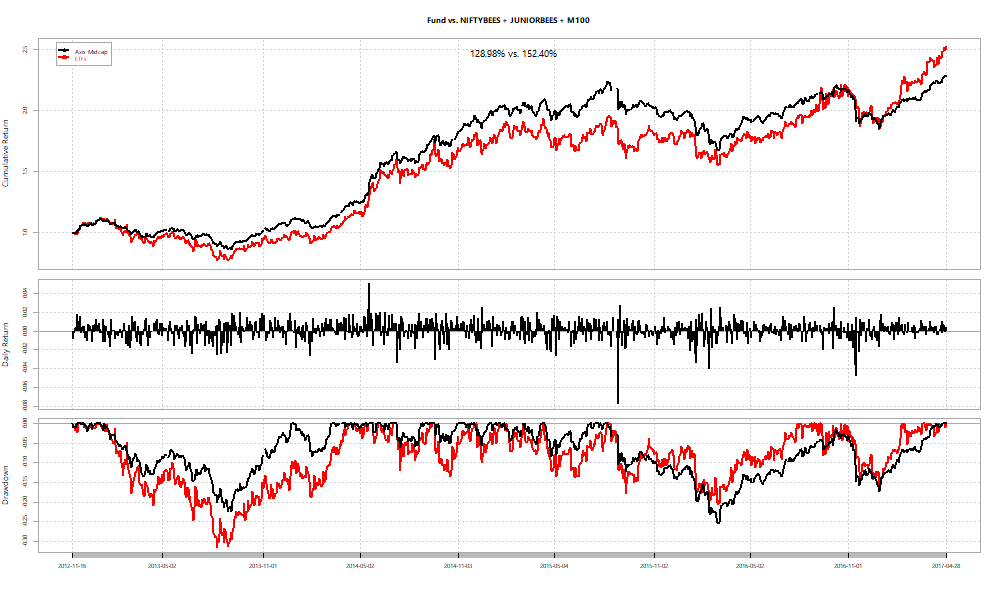

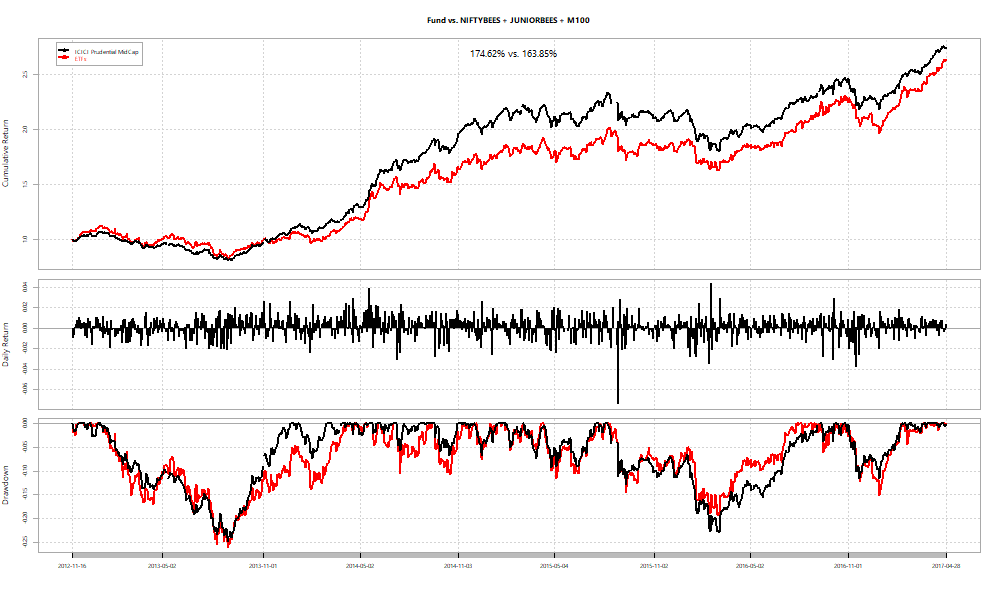

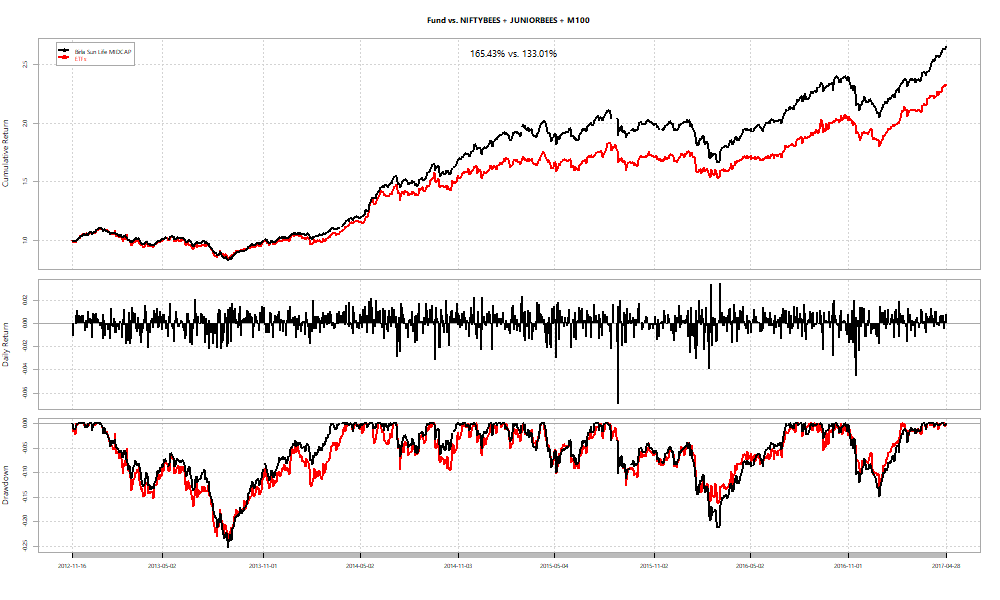

In all cases the basket fixed at the peak performs at par or better than the fund. However, you never really know what the “peak” is when you are living through it. What if you fix the basket right at the beginning?

In two out of three cases, we see funds beat ETF baskets.

Summary

- We use linear regression to measure a fund’s alpha over a basket of ETFs.

- Alpha varies over time. Out/under performance is sensitive to begin and end dates.

- If a fund’s peak alpha can be pegged, then a basket of ETFs with those betas will outperform the fund.