The biggest bet that buy and hold investors of a given country are making is that their government stays committed to increase, preserve and protect their citizen’s wealth. It is a combination of regulation, property rights, human capital, investor sentiment and global capital flows.

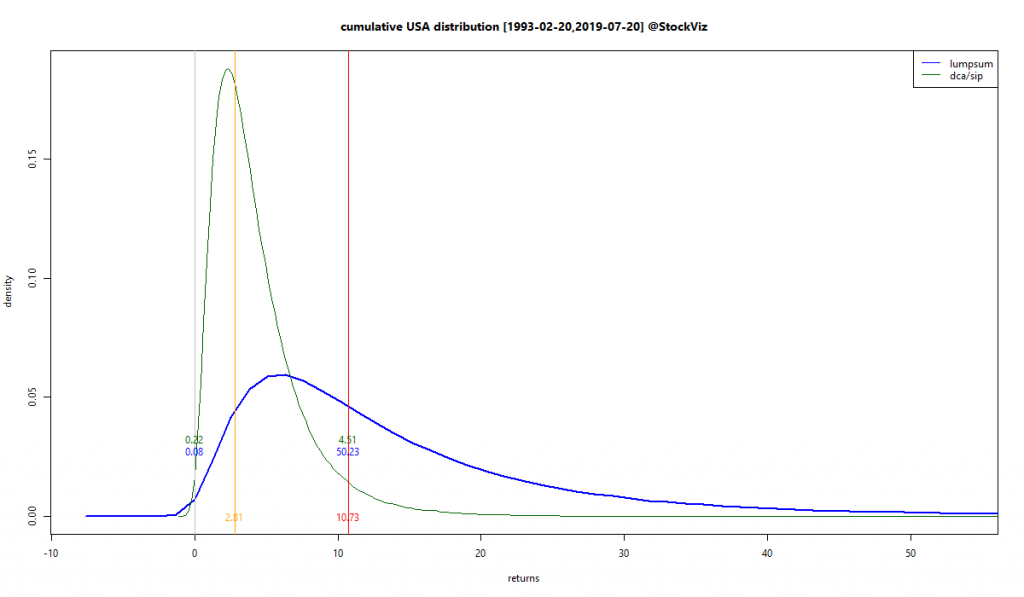

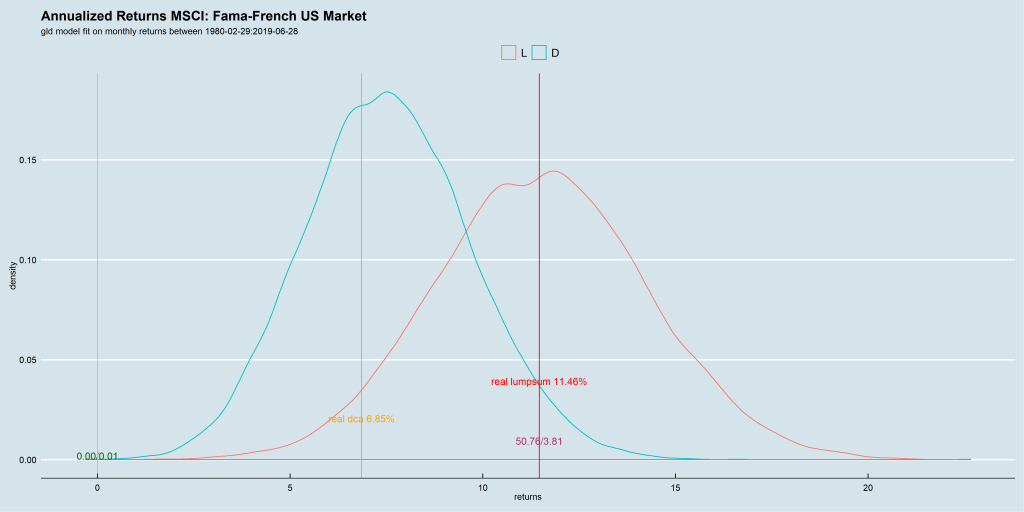

Buy and hold worked out great for US investors in the last 30-years. Inflation was mostly under control and they enjoyed a dollarized world with the rest of the world sending their surpluses to the US. But It wasn’t always like this.

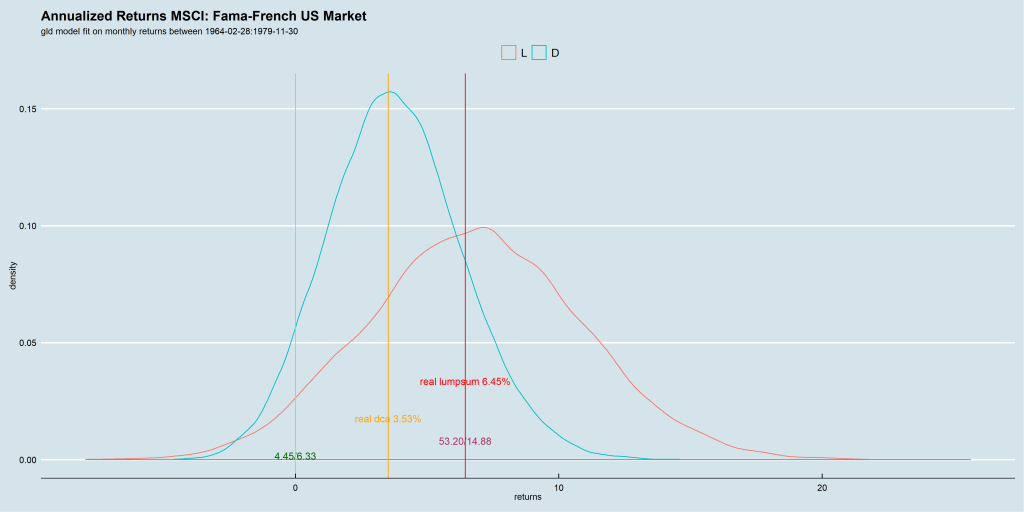

The year 1980 was a turning point for US bonds and equities. Not that there weren’t hiccups along the way – Black Friday, tech bust, GFC, etc – but it was the beginning of a huge tail-wind that continues to blow even today. Compare the simulation results of pre-1980 equity returns vs. what came next:

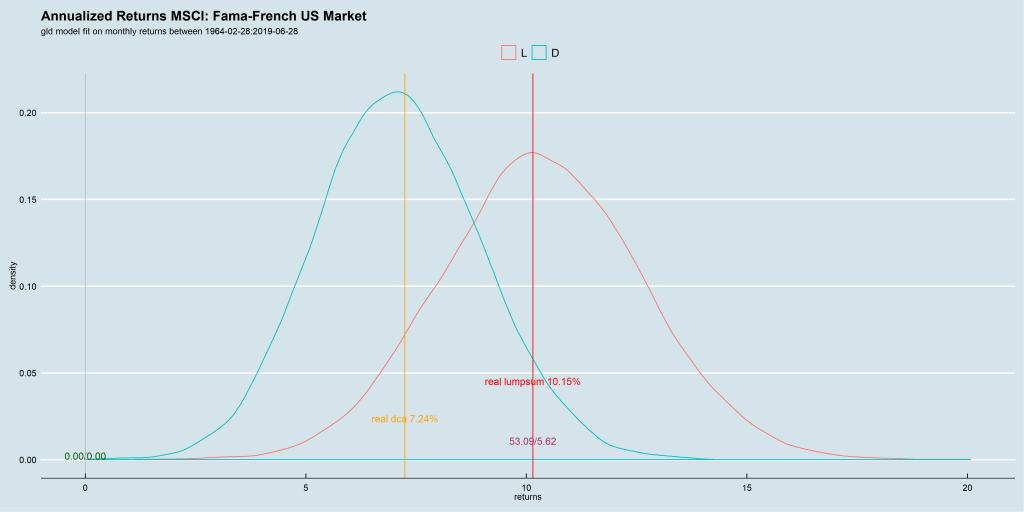

The post 1980 data-set is so skewed that when you use the entire data-set – 1964 through 2019 – for running the simulation, you end up with a 0% loss as well.

With this data-set, it is easy to conclude that a buy-the-market “passive” buy-and-hold strategy is superior to everything else. But that would be a very aggressive conclusion to draw.

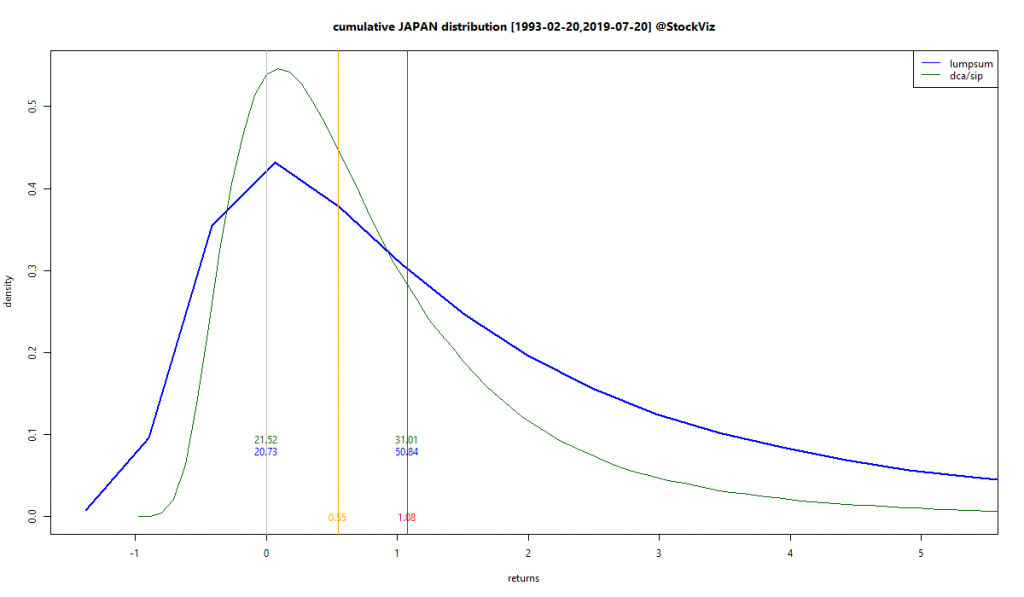

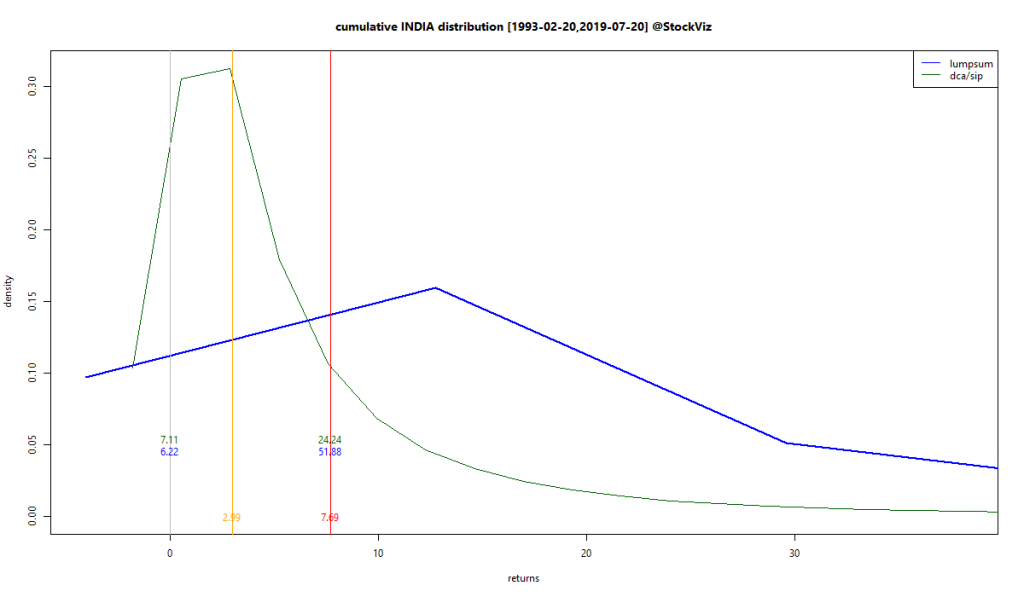

There are quite a few countries with equity returns (since 1993) in the low single digits: GREECE, CHINA, JORDAN, JAPAN, IRELAND, AUSTRIA, PAKISTAN.

CHINA, a country that grew its GDP in double digits, was a very poor equity investment. And JAPAN was the world’s second largest economy in 1995 but their equities are a joke on twitter.

Only DENMARK, USA and SWITZERLAND had an extremely small chance of posting negative buy-and-hold returns.

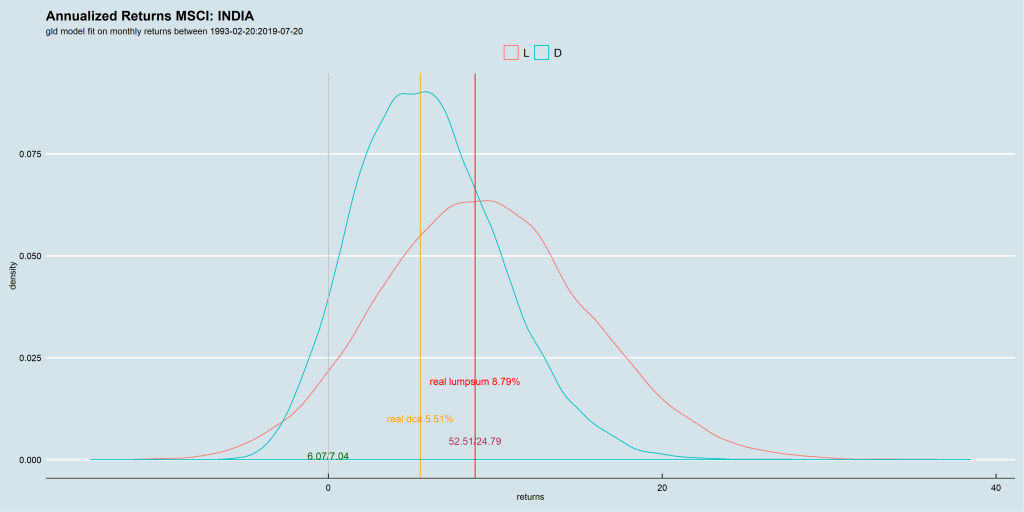

Out of the 43 Country specific MSCI indices we analyzed, half had more than a 10% chance of giving negative returns to buy-and-hold investors. India had a 6% chance.

Any analysis done on US stocks should be taken with a pinch of salt. The rest of the world does not work that way.

This post expands on an earlier one on the same topic.