The VIX is a measure of implied volatility of the underlying index. For example, the CBOE Volatility Index is a measure of 30-day expected volatility derived from S&P 500 Index call and put option prices, India VIX similarly uses the NIFTY 50 call and put options prices to derive a measure of volatility. The question we will try to address in this series of posts is whether the VIX can be used to time entries and exits on the underlying index.

The VIX time-series

The VIX on S&P 500 has been around since the 90’s whereas India VIX started out around 2009. Moreover, the US enjoys a much wider and deeper market for volatility products than any other market in the world. VIX futures, VIX options, VIX of VIX, volatility ETFs and their inverse, all trade fairly well. Whereas in India, even though VIX futures have been listed for a while, it rarely trades. Trading activity of a derivative (VIX, in this case) invariably has an effect on the underlying (S&P 500, NIFTY 50…) So we expect the relationship between S&P 500 VIX and the S&P 500 index to be closer than that between India VIX and the NIFTY 50 index.

VIX quintiles

To begin, we will bucket the trailing 1000-day VIX closing prices into quintiles and observe the next 5, 10, 15 and 20-day returns of the underlying index over them.

S&P 500 VIX

And, more recently:

What is striking here, is that subsequent returns off the 5th quintile (when VIX is at its highest) is higher with smaller negative outliers than returns off the 1st quintile (when VIX is a its lowest.) This is counter-intuitive to the notion that “volatility begets volatility” so investors are better off staying away from the market when it is volatile.

India VIX and NIFTY 50 shows a similar pattern*:

*Smaller sample compared to the S&P 500 dataset.

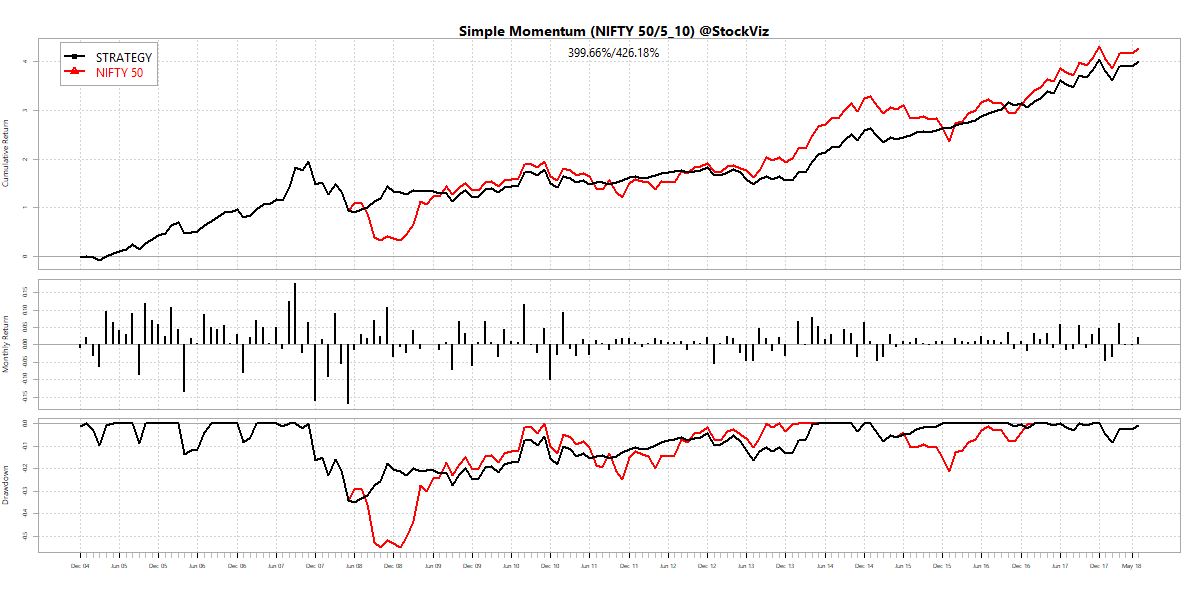

A simple back-test

What happens to a long-only portfolio if it is long the index only when the VIX is within a particular quintile?

S&P 500/VIX

The strategy that is long when VIX is in the 5th quintile (L5) out-performs the other quintile strategies. Also, if you ignore the 2008 collapse, L5 has the shallowest of drawdowns.

NIFTY 50/VIX

Something similar happens with NIFTY 50 as well:

Implications

Cash-only investors can point to the superiority of buy&hold compared to these VIX-based strategies. However, the shallow drawdowns exhibited by the L5 strategy (long index when VIX is in the 5th quintile) is attractive to leveraged traders. For example, NIFTY 50 futures leverage is between 8x and 10x. So even if you play it safe and leverage only 5x, L5 returns would end up at ~100% compared to buy&hold’s 80% over the same period.

We will dig deeper in the next part of this series. Stay tuned!

Code and more charts are on github.