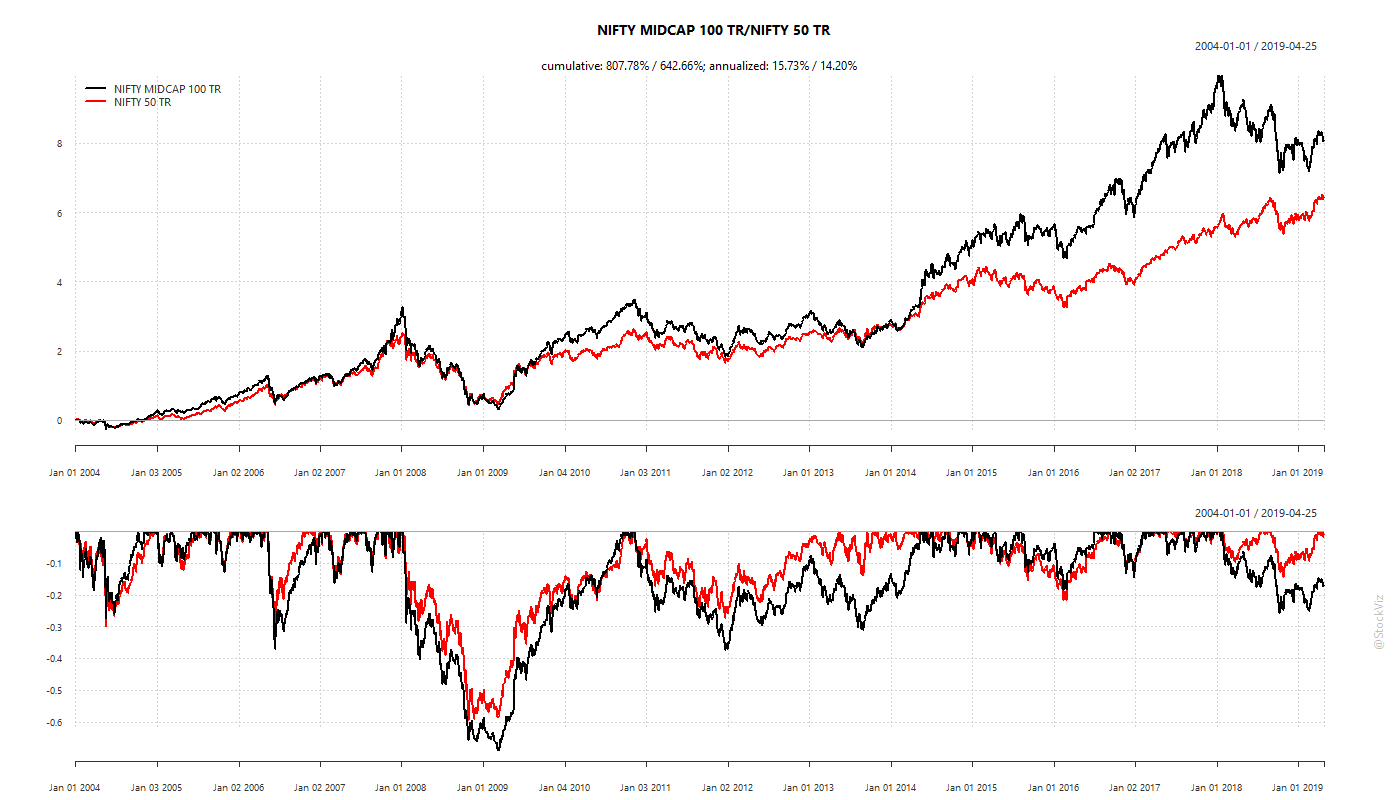

We saw how, in aggregate, stop-losses do not add any value to a momentum portfolio after taxes and transaction costs (Are Stop-Losses Worth It?) When you dig a little deeper into the actual positions that get stop-lossed and analyze their subsequent returns, we find that, on average, subsequent returns are not negative enough to justify trading costs.

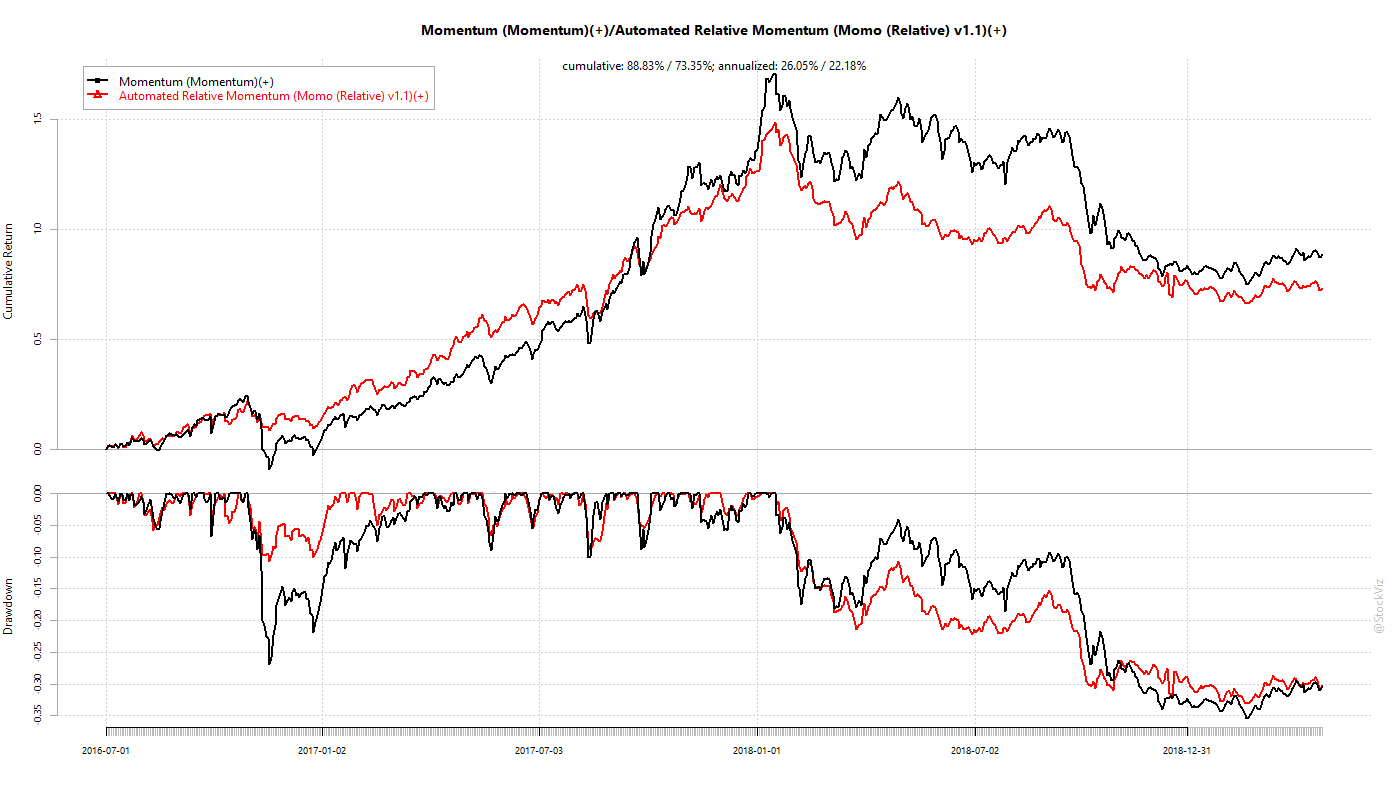

During mid-2016 through April-2019 Bull and Bear phases

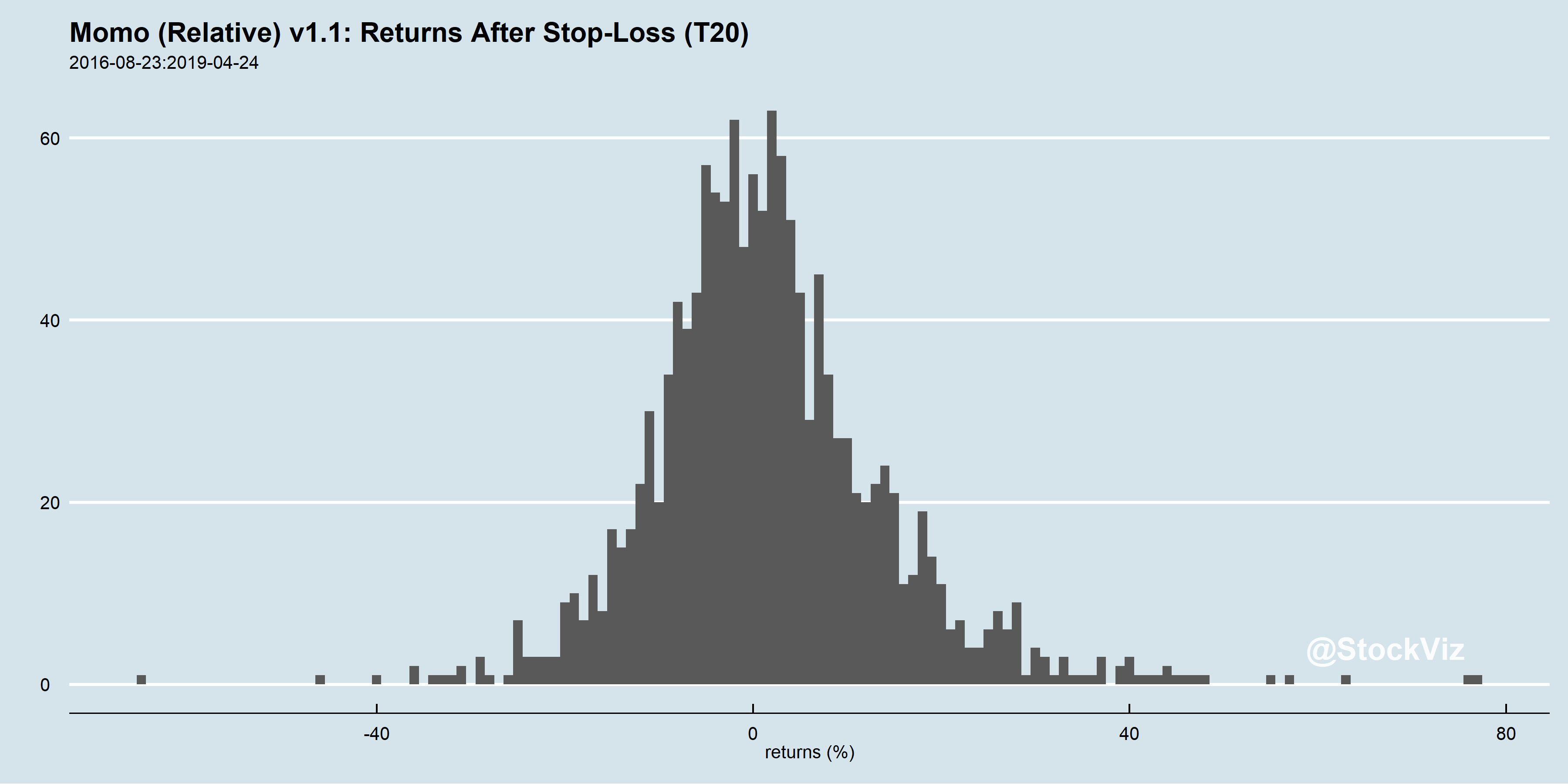

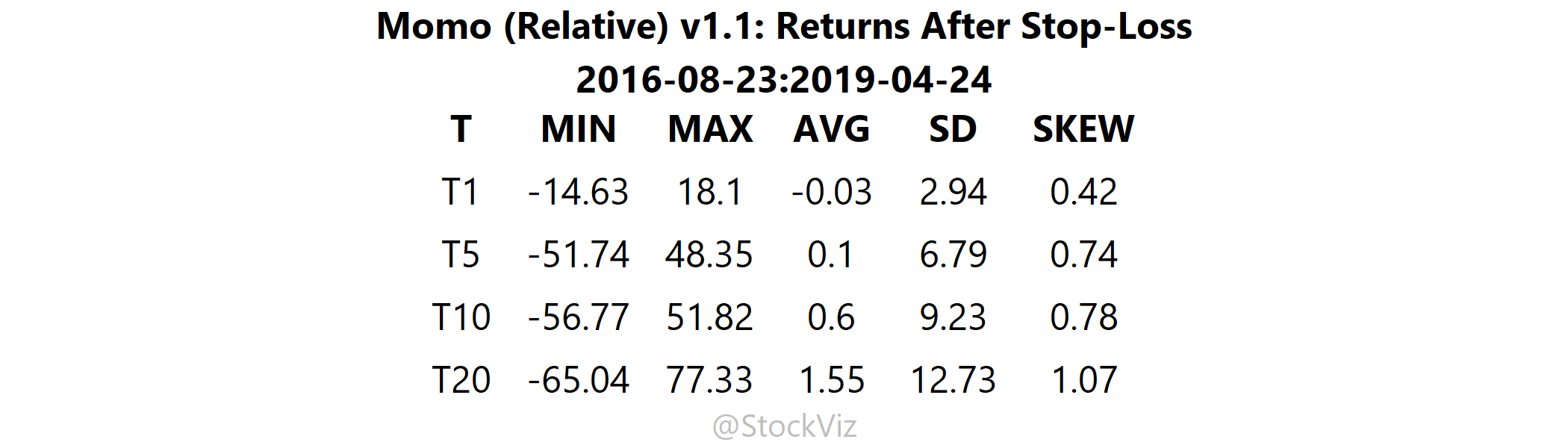

Here’s how the Momo (Relative) v1.1 Theme’s stop-lossed positions behaved 20-days after they got booted out, mid-2016 through April-2019:

Summarized statistics across different holding periods:

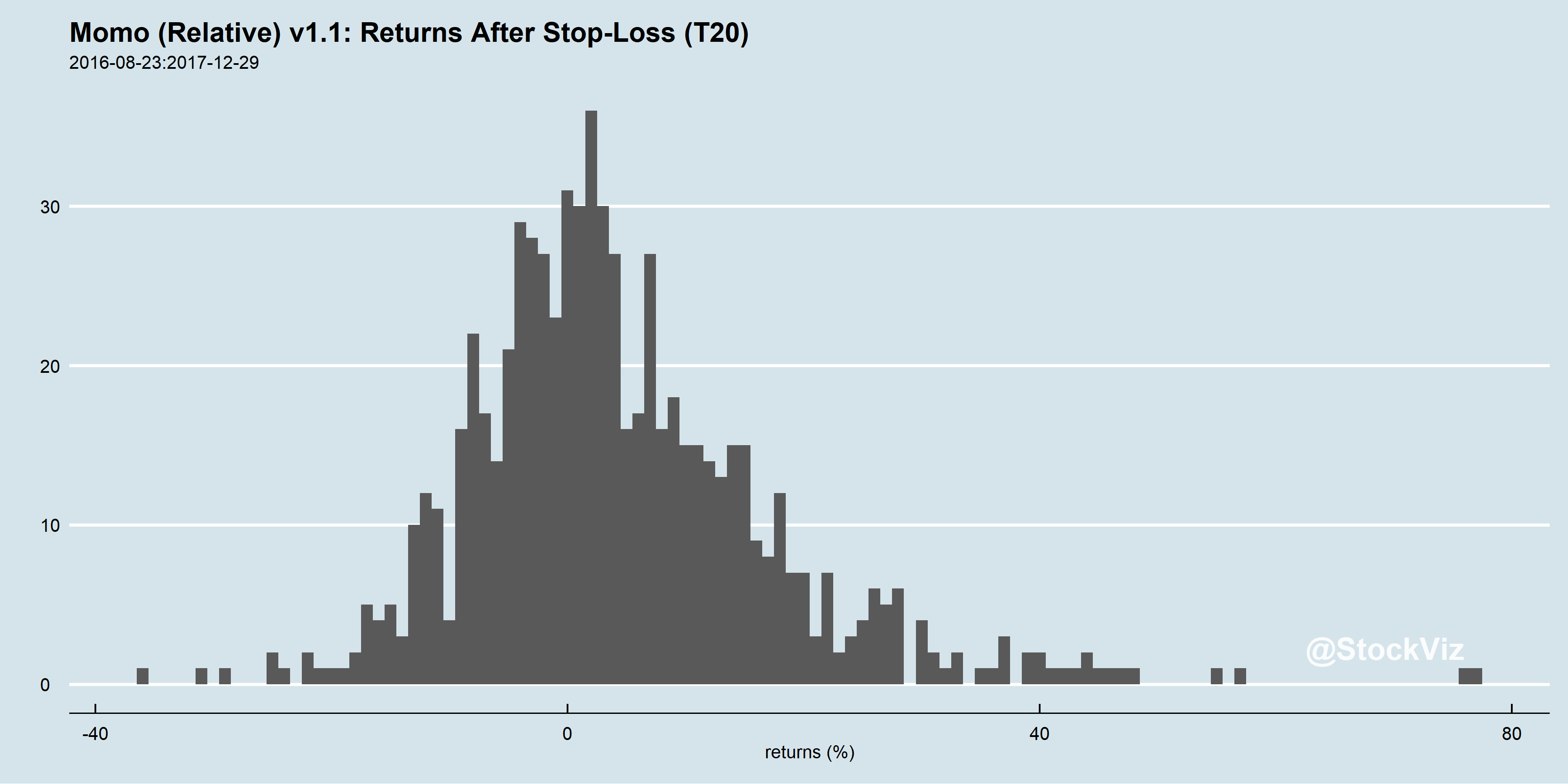

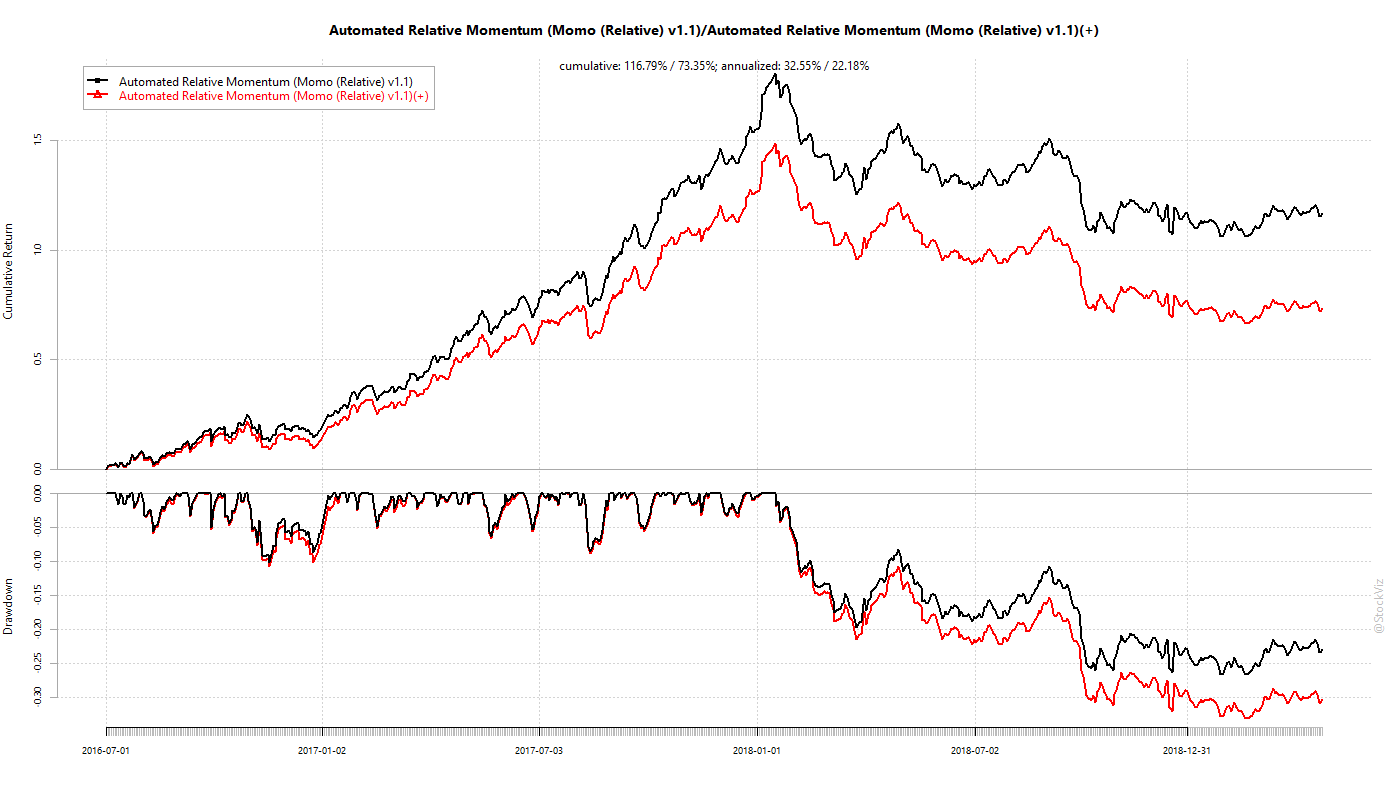

Now let’s partition the total period into two. The first part covers the “bullish” market of mid-2016 through Dec-2017 and the second Jan-2018 through April-2019.

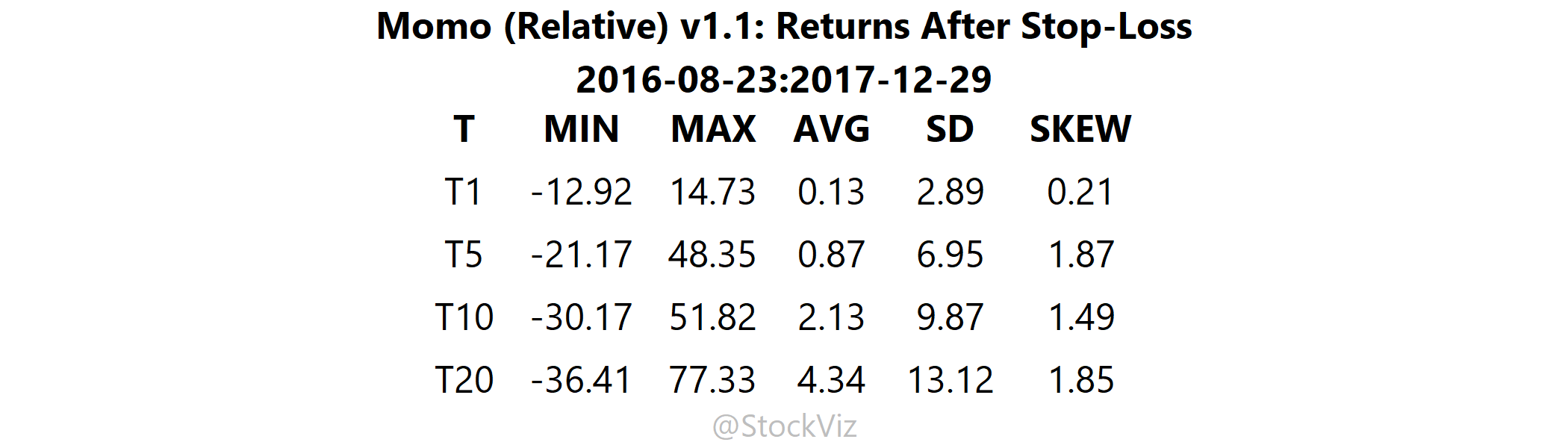

During the mid-2016 through Dec-2017 Bull

Summarized statistics across different holding periods:

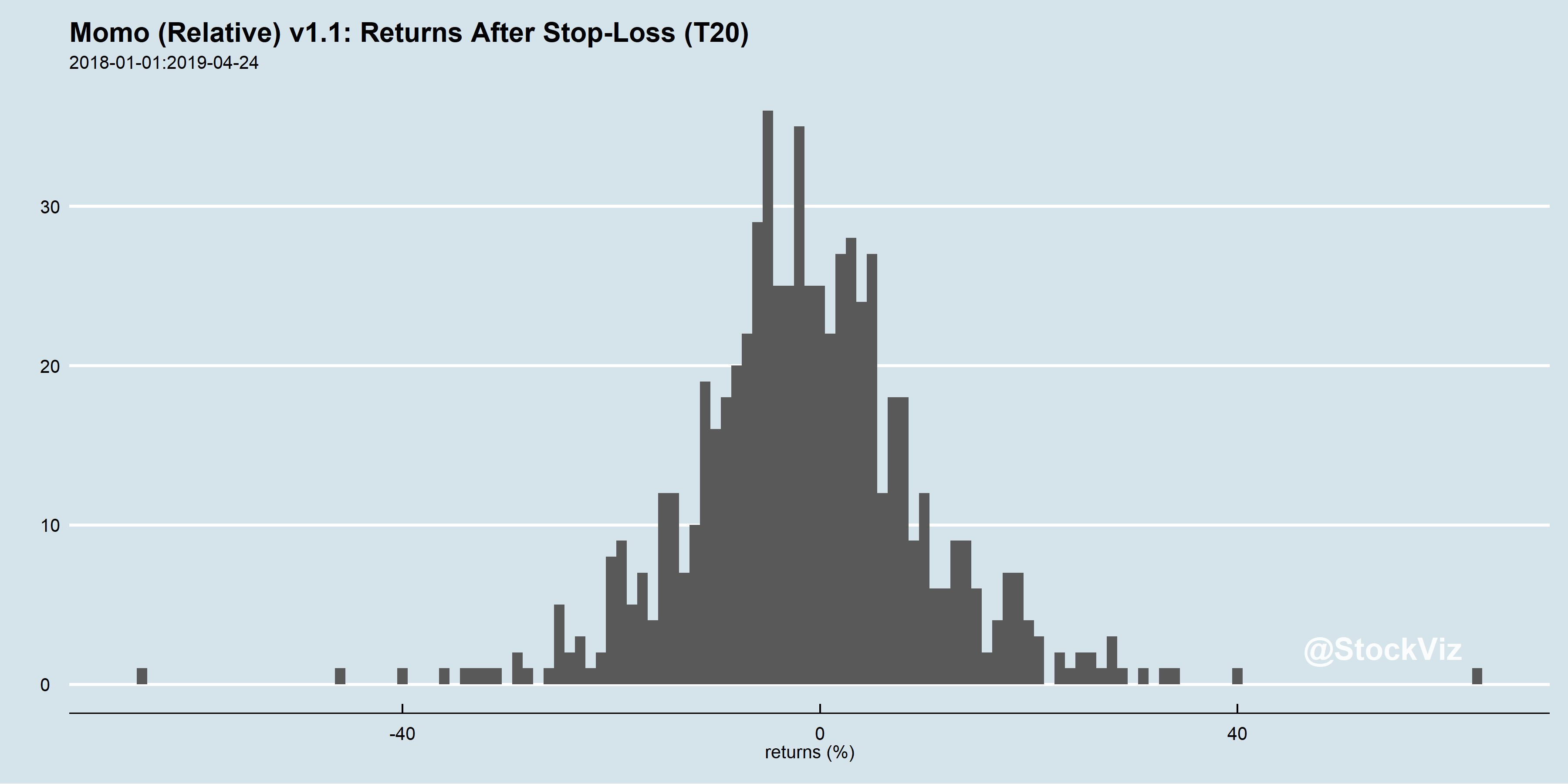

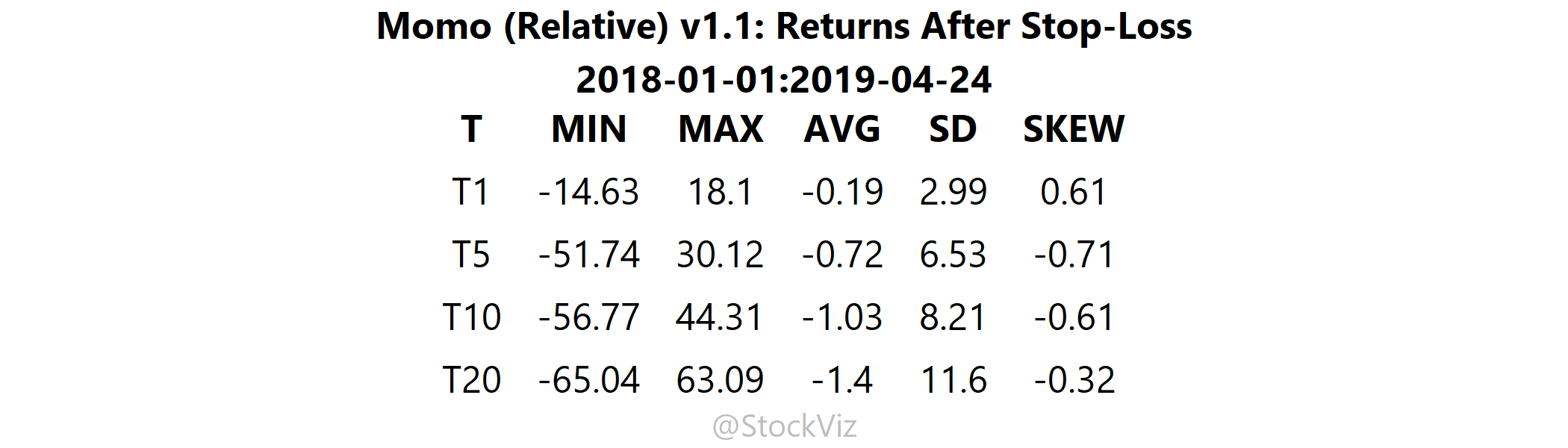

During the Jan-2018 through April-2019 Bear

Summarized statistics across different holding periods:

Conclusion

When looked at from the perspective of a single position, a stop-loss removes red ink and is out-of-sight/out-of-mind. However, it is only when you look at their subsequent returns in the aggregate, that you realize that peace-of-mind comes at a cost.

During the bull phase, when the whole market was shooting higher, stop-lossed positions recovered from their losses. Note how the skew is slightly positive. Stop-losses here were a definite drag after taking costs into account.

During the bear phase, it does look like stop-losses helped – the subsequent returns of stop-lossed positions were skewed left. However, as we saw in our previous post, in aggregate, they did not add value after taking costs into account.