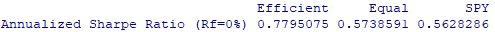

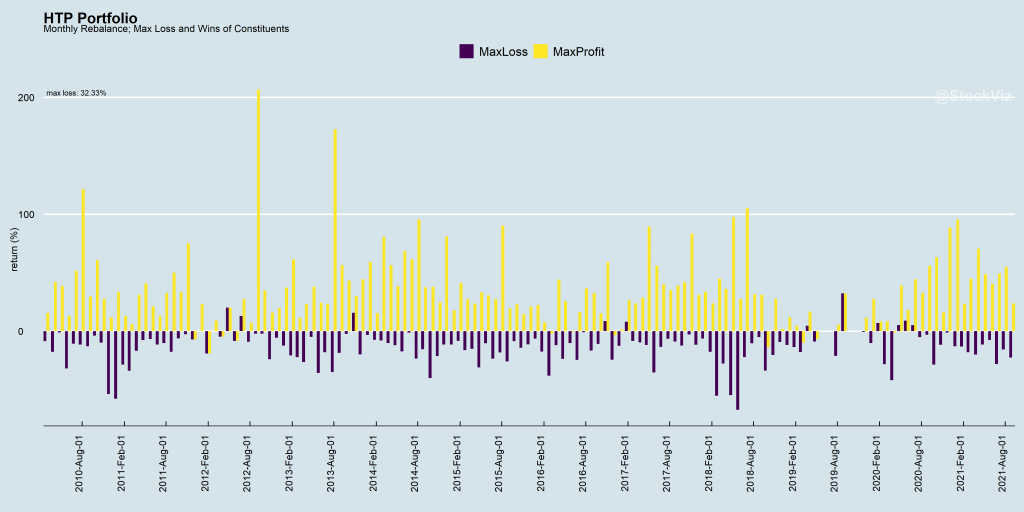

We’ve been having a bit of fun with the S&P Sector “Spider” ETFs: Intro, Momentum, Anti-Momentum. We saw how strategies that backtested well with pre-2011 data failed later. In this post, we see if buying all ETFs with a positive return over n-months help us beat the S&P 500 index.

Rules of Rotation

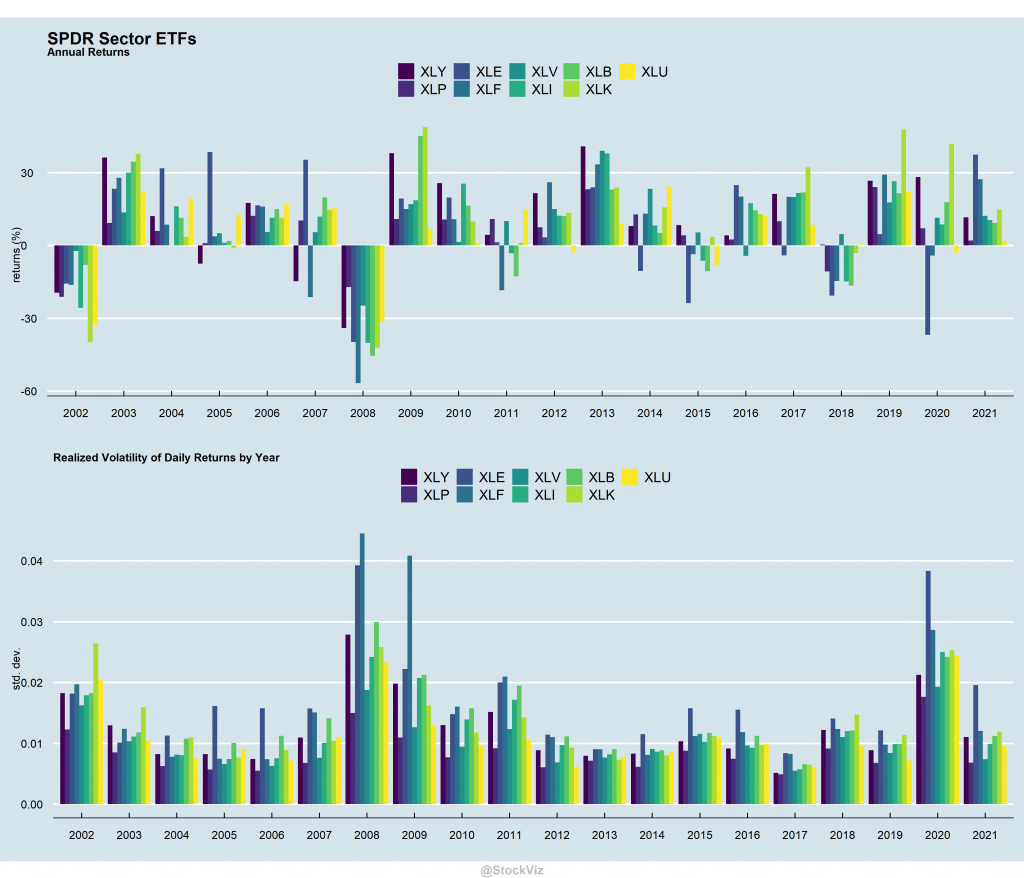

For ETFs: XLY, XLP, XLE, XLF, XLV, XLI, XLB, XLK, XLU

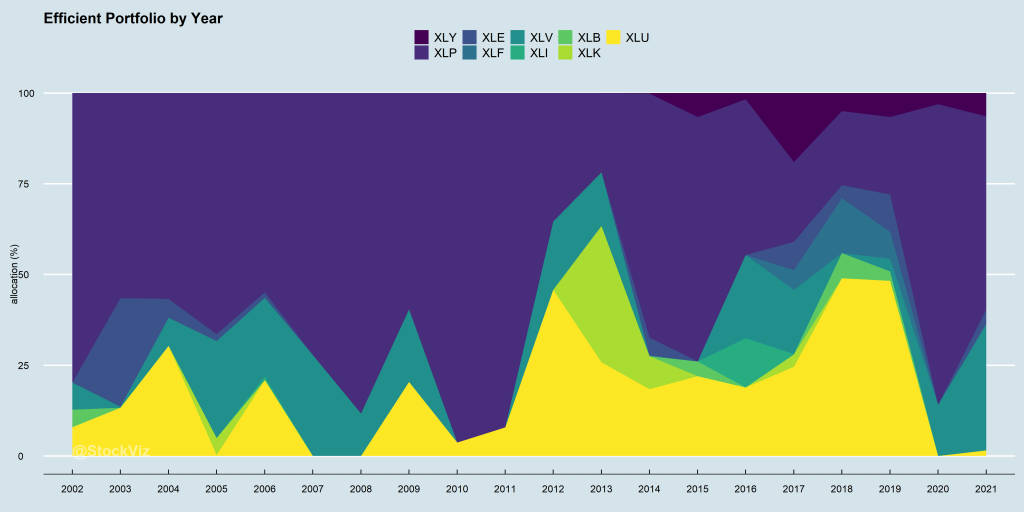

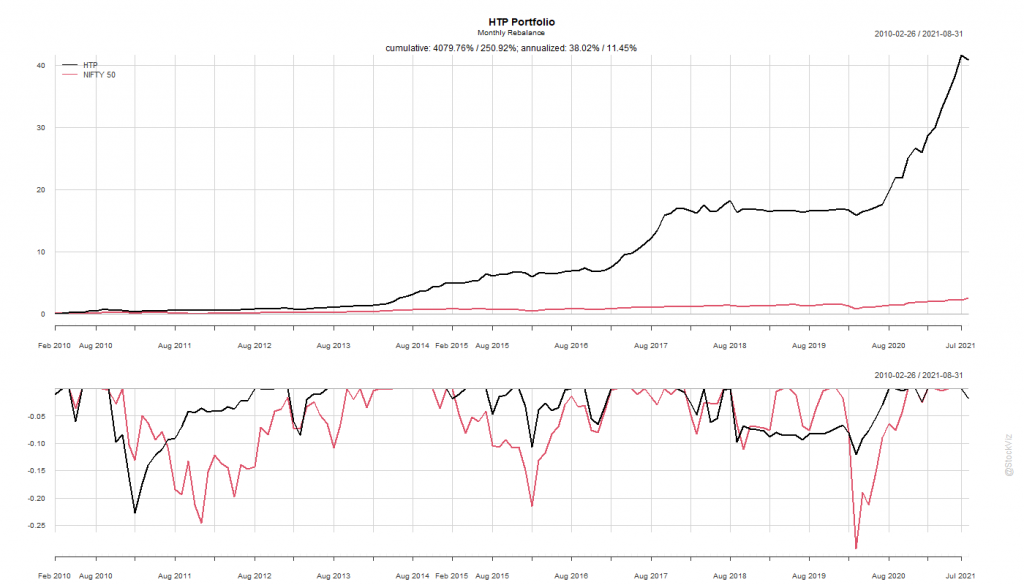

- Calculate rolling returns over n months. Where n = 1, 3, 6, 12.

- For the n+1th month, go long the ETFs that had positive returns in Step 1.

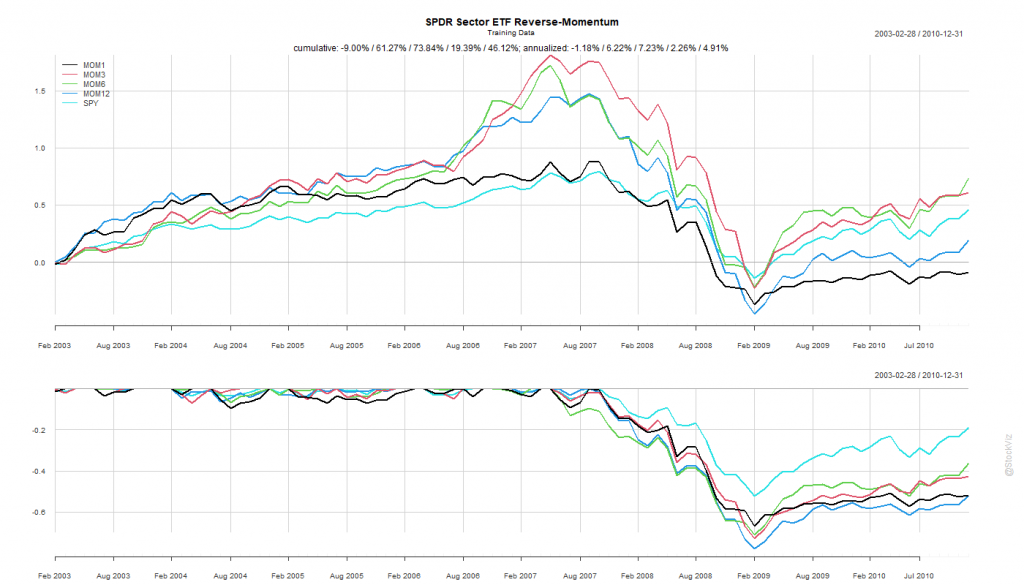

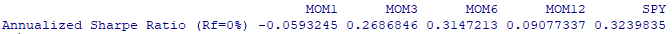

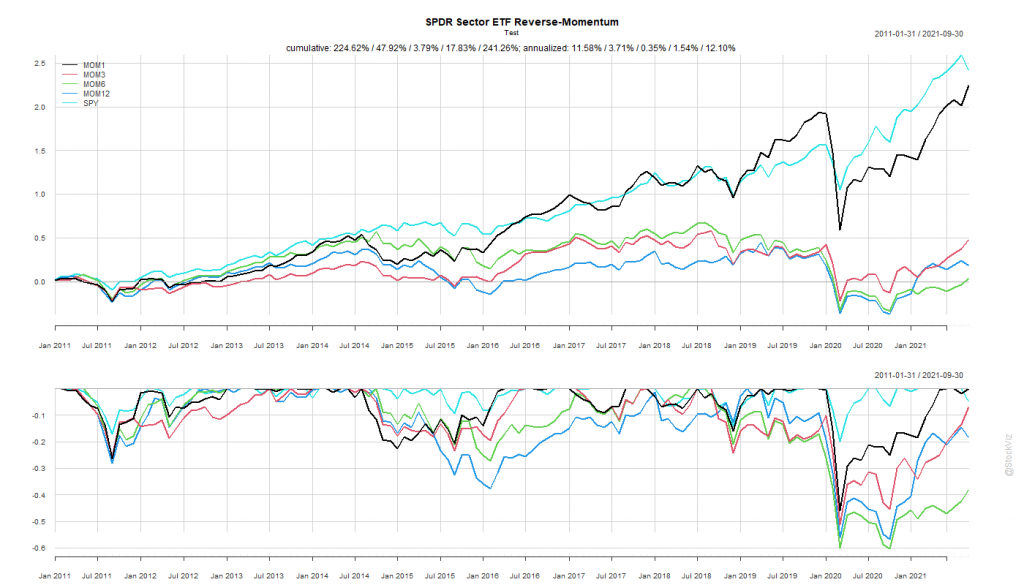

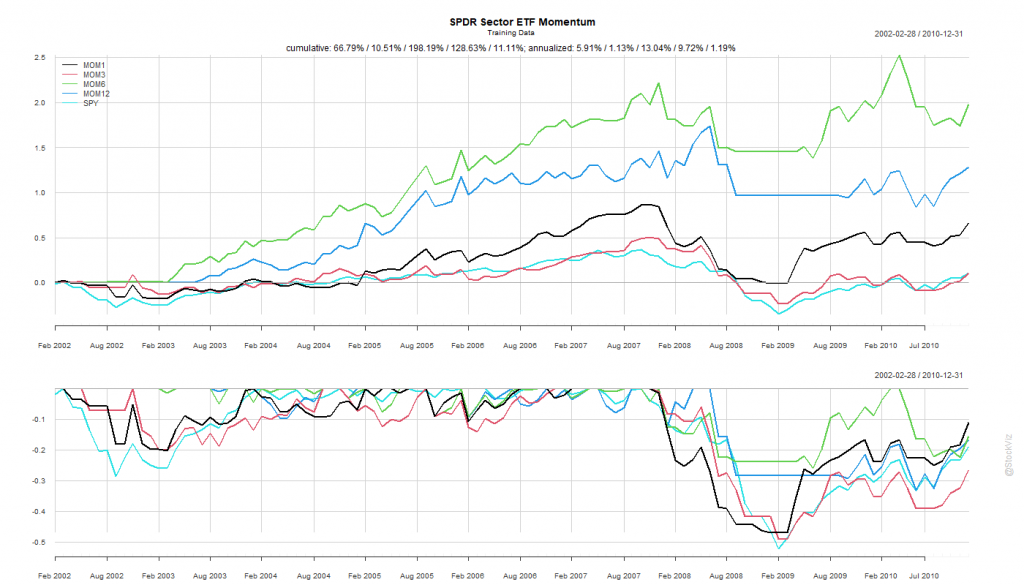

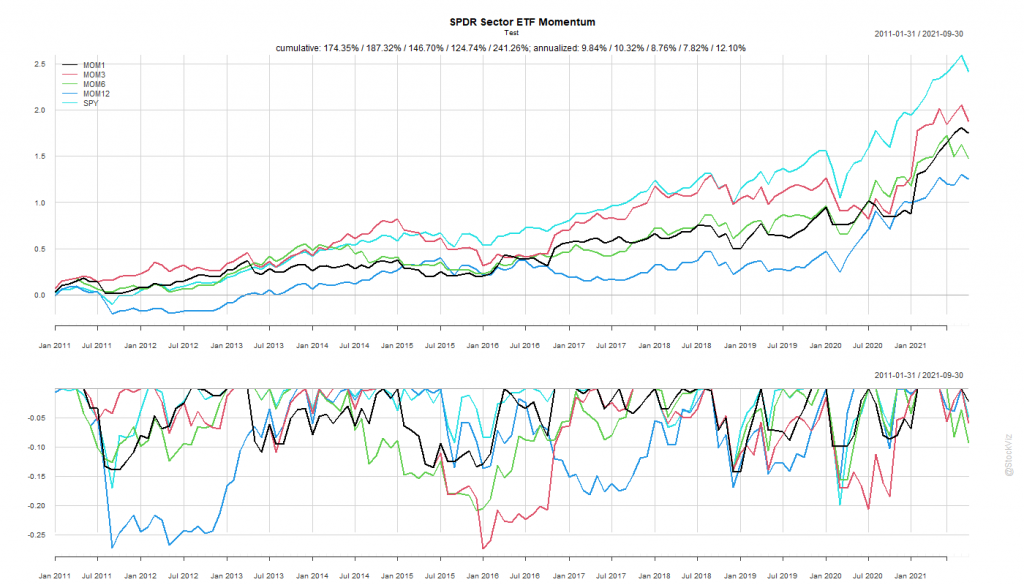

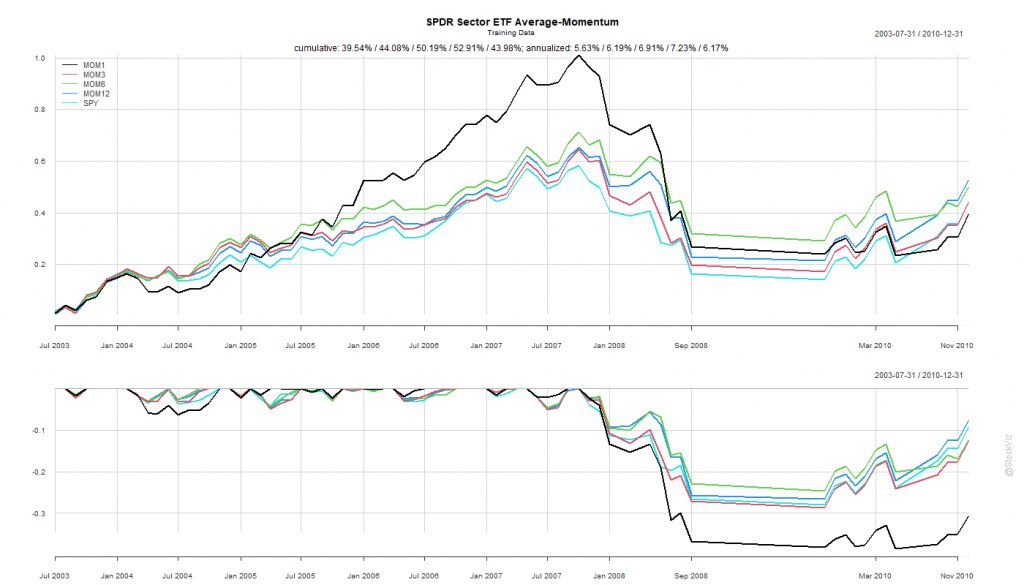

Like before, we split the dataset into Before 2010 and After 2011.

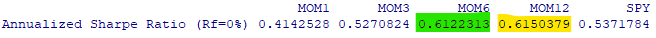

Pick your Fighter

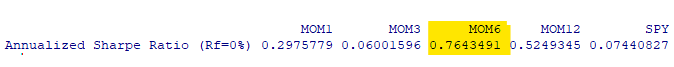

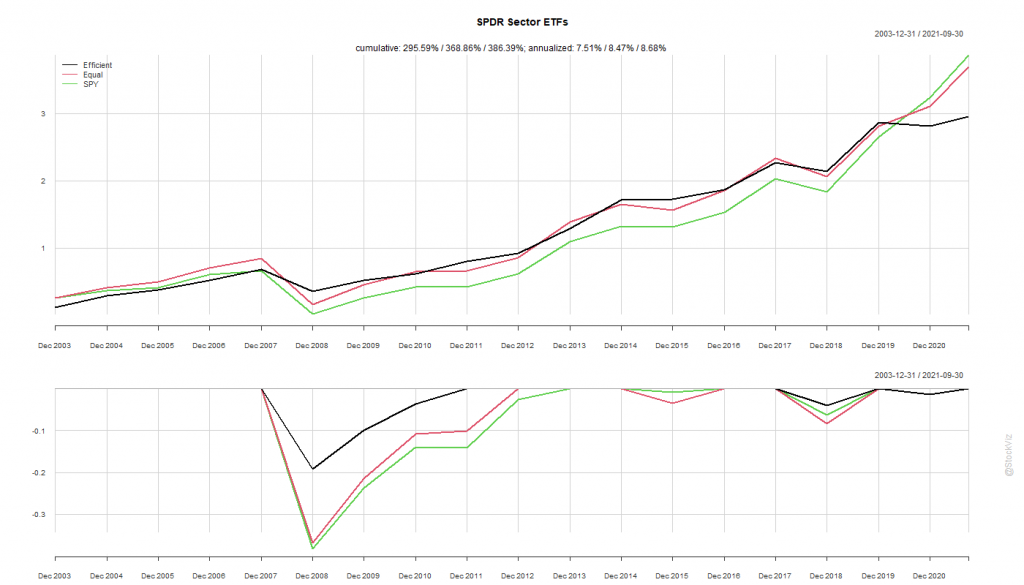

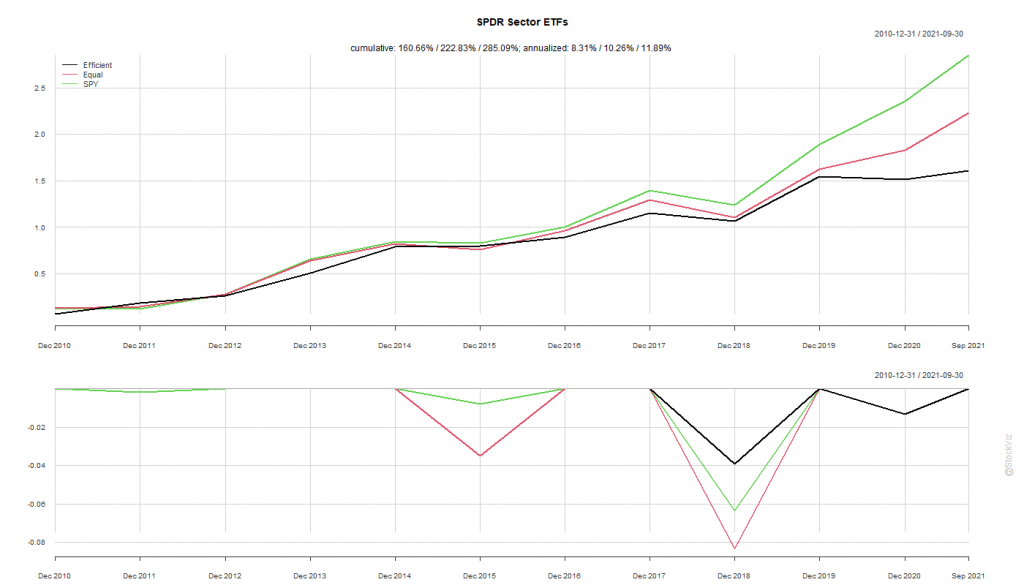

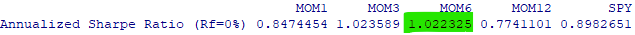

The Before 2010 dataset shows rotation by 6- and 12-month look-back periods to be better than buying-and-holding the S&P 500.

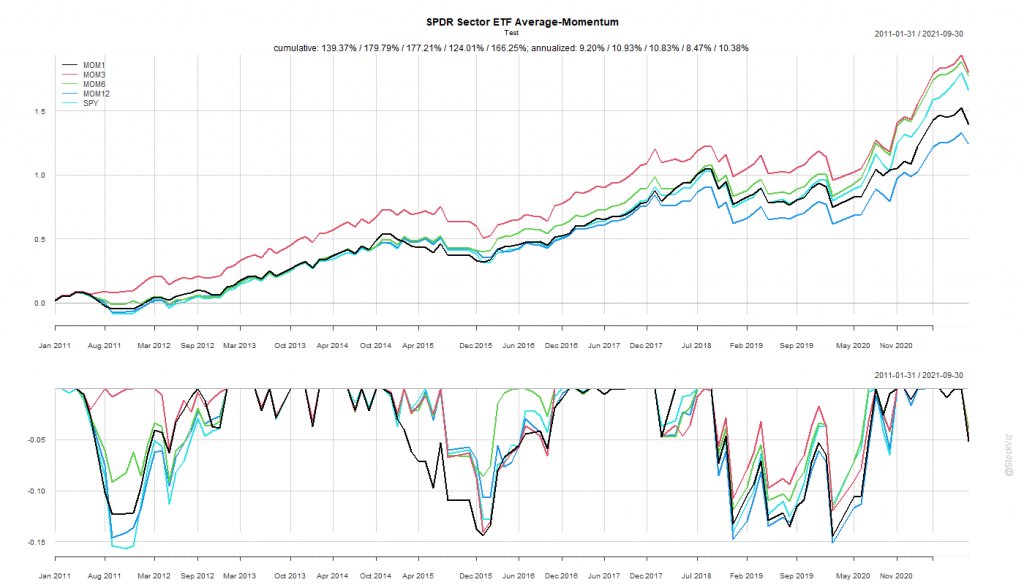

The SPY Rope-a-Dope

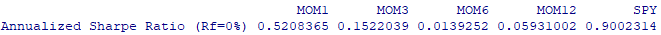

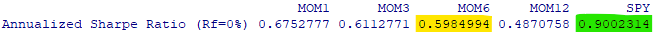

MOM6 and MOM12 were too close to call in the training set. If you had “course-corrected” after the first couple of years of under-performance of MOM12 and switched to MOM6, you would’ve out-performed. On the other hand, staying the course would’ve meant losing out to the mighty S&P 500.

What did we learn?

We tested a few basic allocation strategies that investors typically use to approach the “rotation” problem. Some of them worked well in the training set but their performance failed to carry over. Besides, if you add transaction costs and taxes, we are not sure if it was worth the effort given the post-2011 market regime.

Maybe there are more sophisticated qualitative/fundamental ways to approach this problem that work. However, most media articles about “sector rotation” are written with perfect hindsight and it is near impossible to do it with simple strategies that are accessible to the average investor.