Trend-following systems typically use the past performance of a particular asset to trigger a buy or a sell on that asset. A research paper that came out in 2019 looked at whether the historical performance of multiple assets can be used to trade them.

Pitkäjärvi, Aleksi and Suominen, Matti and Vaittinen, Lauri Tapani, Cross-Asset Signals and Time Series Momentum (January 6, 2019). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2891434

From the abstract:

We document a new phenomenon in bond and equity markets that we call cross-asset time series momentum. Using data from 20 countries, we show that past bond market returns are positive predictors of future equity market returns, and past equity market returns are negative predictors of future bond market returns.

Unfortunately, the paper did not look at Indian markets to check if this worked. So, we rigged up a simple backtest to see for ourselves.

Rules

A simplified equity-bond cross-asset trading strategy at the beginning of month t can be constructed as follows: Compute the past 12-month equity return (E past) and the past 12-month bond return (B past). If:

a) E past is positive and B past is positive: Buy equity

b) E past is negative and B past is negative: Sell equity

c) E past is negative and B past is positive: Buy bonds

d) E past is positive and B past is negative: Sell bonds

e) Otherwise, invest in the risk-free rate.

Hold the portfolio for one month and then repeat the same procedure in month t+1 (source.)

Backtest

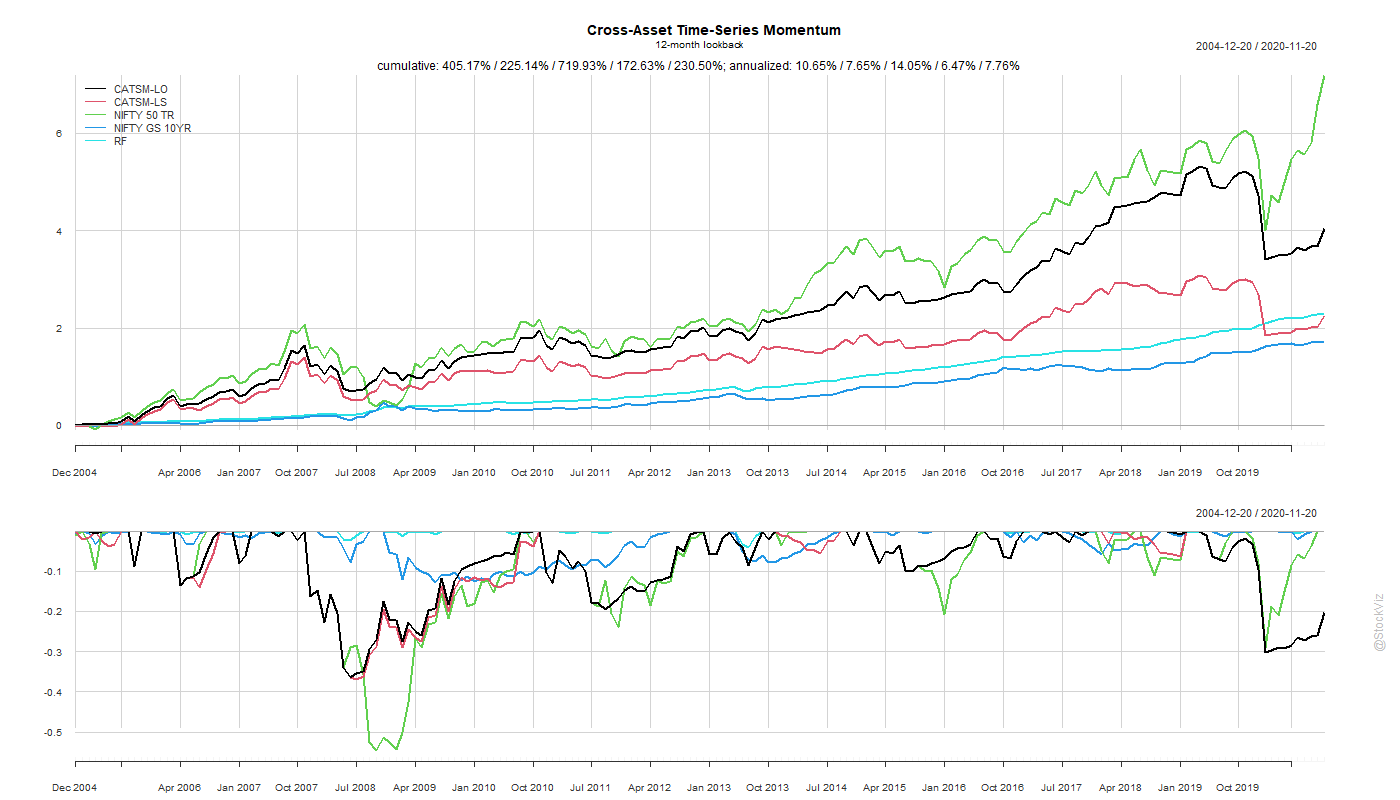

We used the NIFTY 50 TR index to represent equities, NIFTY GS 10YR index for bonds and the CCIL Index 0-5 TRI for risk-free rate.

Since our risk-free index starts only from 2004, our backtest only goes back 16 years. However, the markets have been through a lot since then, so it is unlikely we are losing much by not being able to go back much earlier.

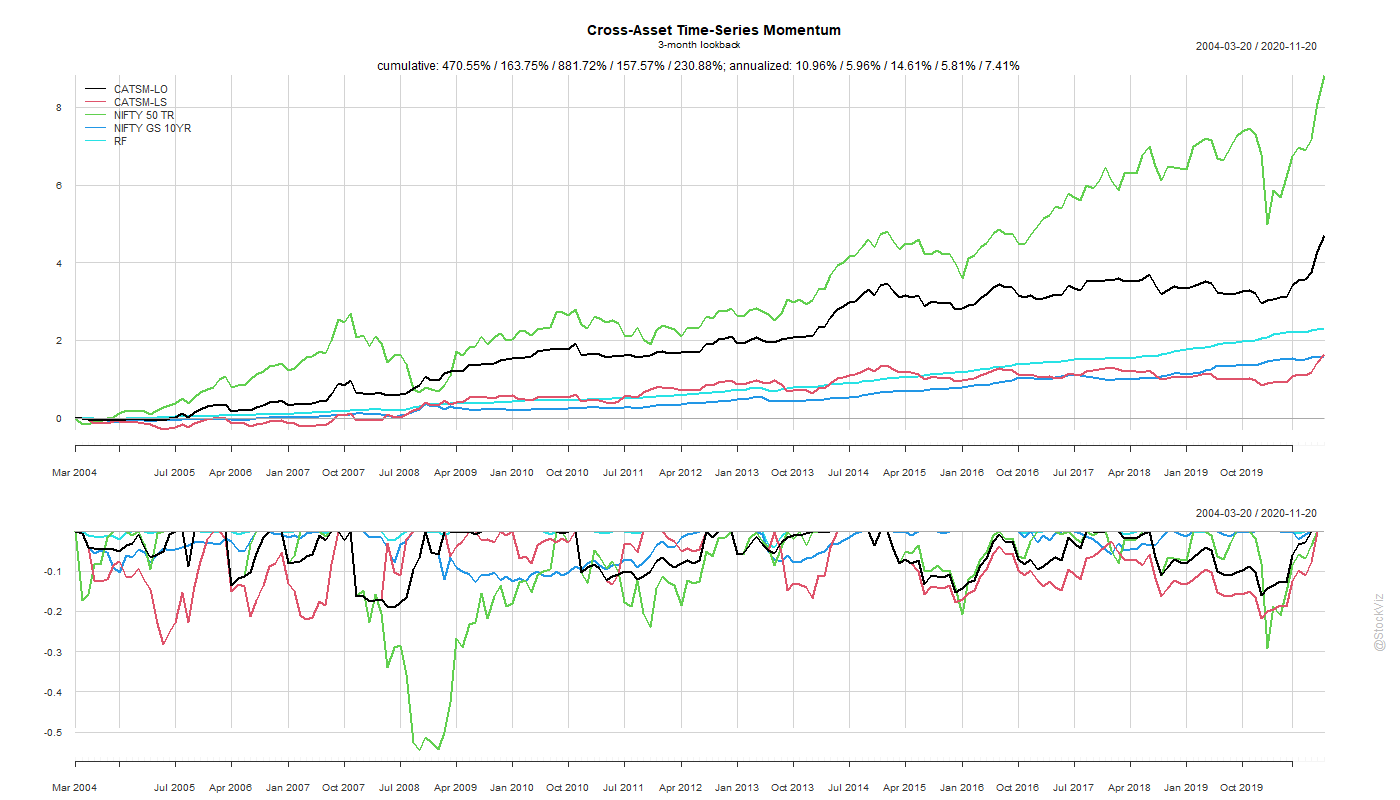

The 12-month look-back approach massively under-performs the NIFTY 50 TR buy-and-hold. We shortened the look-back to 3-months to see if we could make the strategy more responsive to trend reversals.

To our dismay, we saw only marginal improvements in overall returns but the draw-down profile of the long-only portfolio was much better.

Conclusion

While the approach outlined in the paper might be valid for the selected subset of markets, it fails a simple backtest on Indian market indices.

Code for the backtest can be found on github.