We recently discussed linear regression by using it to inspect the relationship between two banking stocks. Lets try and extend that treatment to an index and its predominant constituents.

Bank Nifty

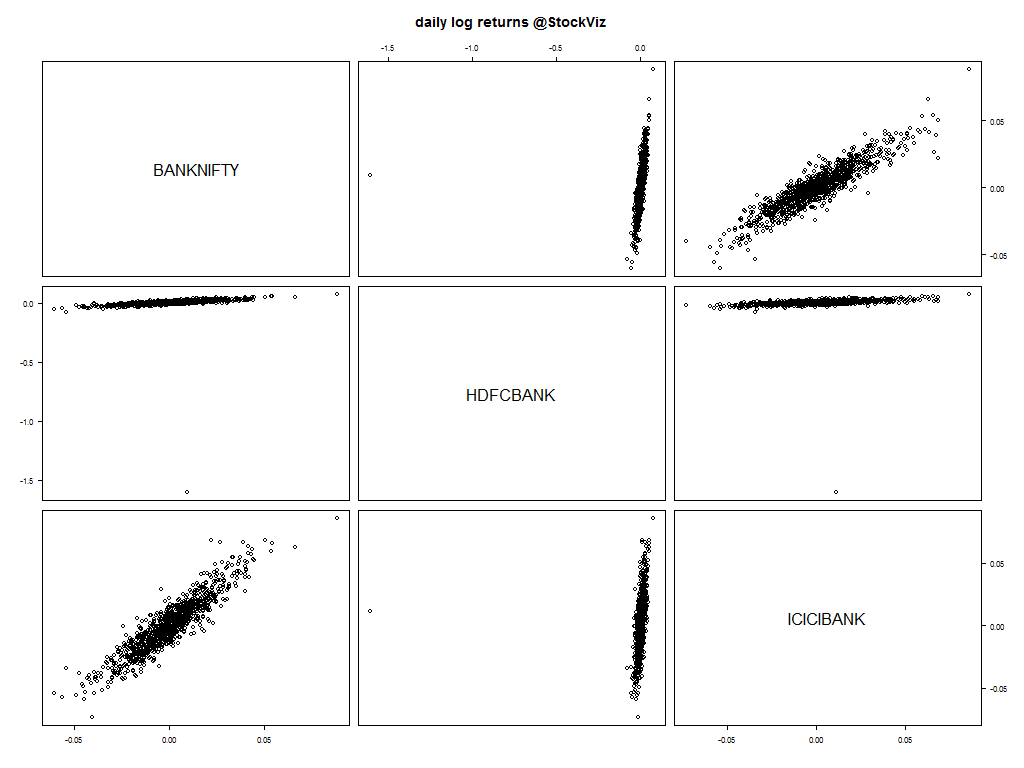

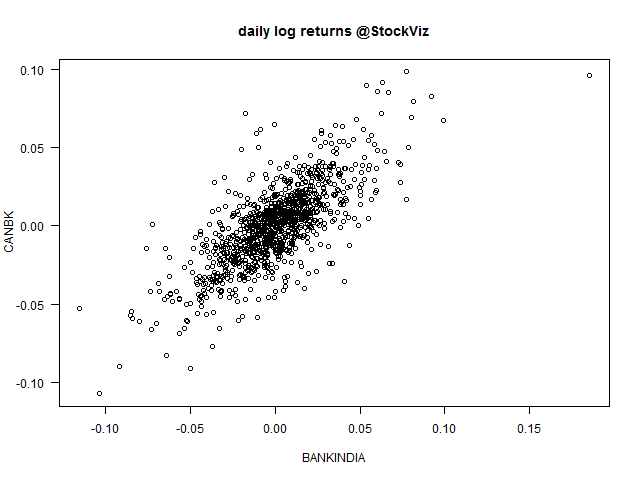

The Bank Nifty is composed of 12 bank stocks with ICICIBANK and HDFCBANK making up 29.27% and 28.26% of the index, respectively. Lets start with the scatterplot of daily log returns of the nearest to expiration futures.

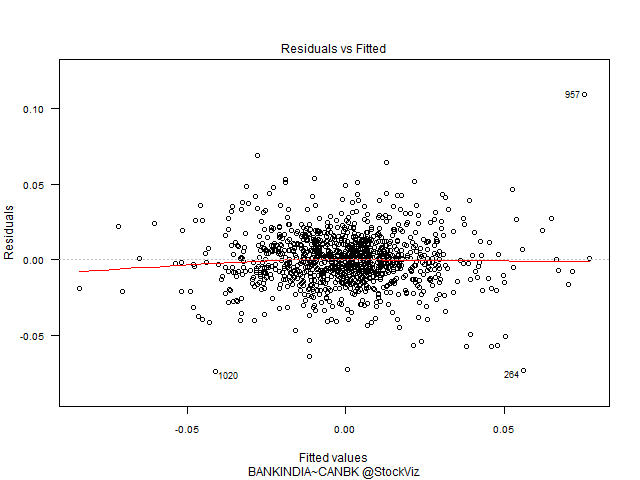

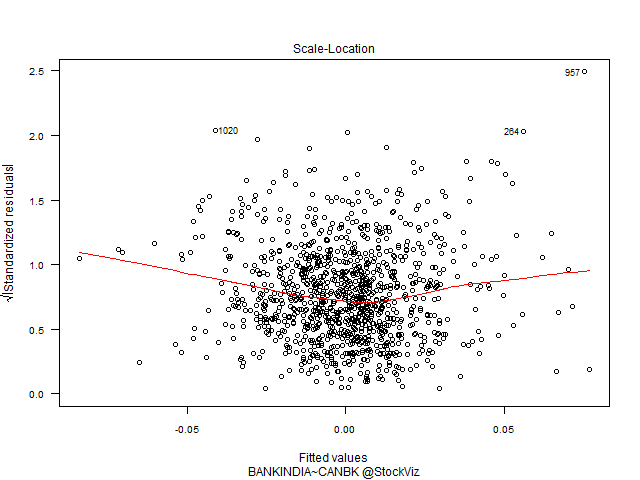

Notice the strong relationship between the index and the banks?

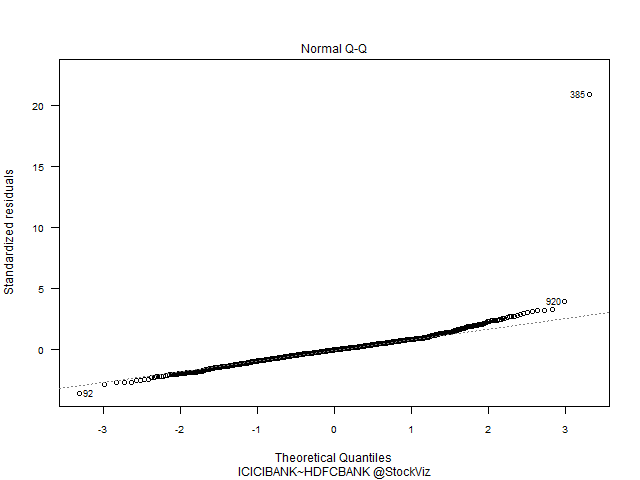

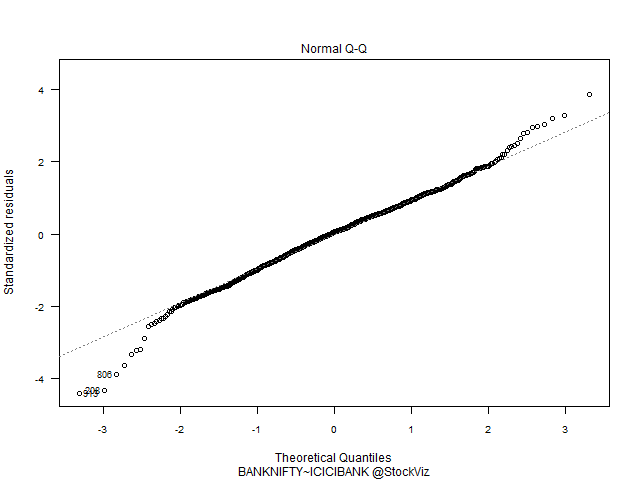

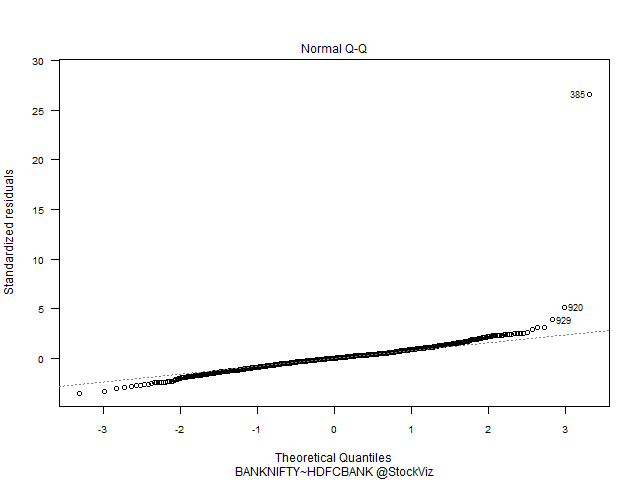

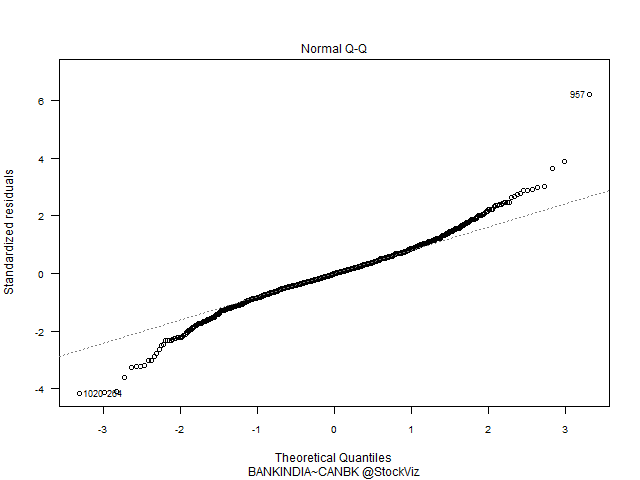

Q-Q Plots

Index vs. Banks have a predominantly Gaussian distribution. HDFC vs. ICICI – not so much.

Pairs trading

With this knowledge in hand, can we trade pairs made out of these three? The rules for pairs trading is fairly straightforward:

- find stocks that move together

- take a long–short position when they diverge and unwind on convergence

The execution of a pairs trading strategy involves answering these questions:

- How do you identify “stocks that move together?”

- Should they be in the same industry?

- How far should they have to diverge before you enter the trade?

- When is a position unwound?

Bank Nifty, HDFC Bank and ICICI Bank certainly fit the criteria.

Co-integrated prices

If the long and short components fluctuate due to common factors, then the prices of the component portfolios would be co-integrated and the pairs trading strategy should work.

If we have two non-stationary time series X and Y that become stationary when differenced (these are called integrated of order one series, or I(1) series) such that some linear combination of X and Y is stationary (aka, I(0)), then we say that X and Y are cointegrated. In other words, while neither X nor Y alone hovers around a constant value, some combination of them does, so we can think of cointegration as describing a particular kind of long-run equilibrium relationship.

For a light introduction to co-integration, read this post on Quora.

To be continued…