Came across this incredible paper by Alan S. Binder, Issues in the Coordination of Monetary and Fiscal Policy, 1982 that uses game theory to explain the relationship between a country’s central bank and the government. It seemed appropriate, given that Raghuram Rajan, the RBI governor, is the same for both the UPA-2 and NDA governments, to study the options before both Rajan and the NDA in framing their relationship.

The paper was written when Regan was the President and Volcker was the chairman of the Federal Reserve. Inflation in 1980 had soared to 13.5% and Volcker had raised the federal funds rate to 20% by June 1981.

The feeling that Rajan and the government are at cross-purposes are echoed in the paper’s introduction:

Now, as often in the past, there are complaints from all quarters about the lack of coordination between monetary and fiscal policy. Indeed, the feeling that monetary and fiscal policies are acting at cross purposes is quite prevalent. This attitude, I think, reflects dissatisfaction with the current mix of expansionary fiscal policy and contractionary monetary policy, which pushes aggregate demand sideways while keeping interest rates sky high.

But how is this game played?

The game being played

The players in this game is Rajan, who sets interest rates, and the politicians, who determine the mix between government spending and tax revenues. Rajan thinks that the control of inflation is his primary responsibility and he’s anyway appointed for a fixed tenure. The politicians, on the other hand, have elections to win, which leads them to favor economic expansion over economic contraction.

The object of the game is for one player to force the other to make the unpleasant decisions. Rajan would prefer to have tax revenues exceed spending rather than to have the government suffer a budget deficit. The politicians, who worry about being elected, would prefer Rajan to keep interest rates low and the money supply ample. That policy would stimulate business activity and employment.

The preferences matrix

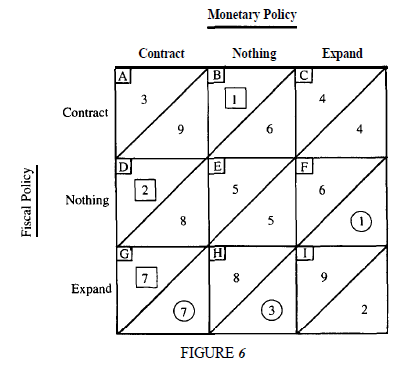

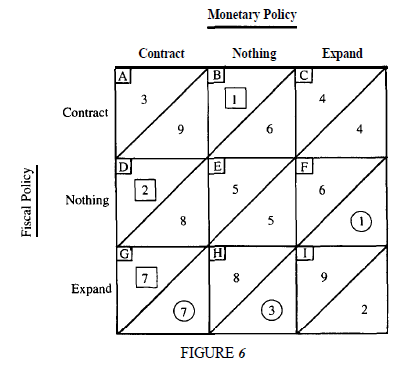

There are 3 decisions in front of each player: contract, do nothing, or expand. The numbers above the diagonal in each square represent the order of preference of Rajan; the numbers below the diagonals represent the order of preference of the politicians.

The highest-ranked preferences of Rajan (A, B, and D) appear in the upper left-hand corner of the matrix, where at least one side is contractionary while the other is either supportive or does nothing to rock the boat. The three highest-ranked preferences of the politicians appear in the lower right-hand corner (F, H and I).

End game

Assuming that the relationship between Rajan and the politicians is such that collaboration and coordination are impossible, the game will end in the lower left-hand corner where monetary policy is contractionary and fiscal policy is expansionary. If Rajan cannot persuade the politicians to run a budget surplus and that the politicians cannot persuade Rajan to lower interest rates, neither side has any desire to alter its preferences nor can either dare to be simply neutral. As long as Rajan is contractionary and the politicians are expansionary, both sides are making the best of a bad bargain. And this is where we were under UPA-2.

The challenge, is to shift the play to the upper right hand corner. Here, neither side is “happy”, but this is the best case scenario – things are stable. This outcome is known as a Nash Equilibrium.

The Nash Equilibrium

Under the Nash Equilibrium the outcome, though stable, is less than optimal. Both sides would obviously prefer almost anything to this one. Yet they cannot reach a better bargain unless they drop their adversarial positions and work together on a common policy that would give each a supportive, or at least a neutral, role that would keep them from getting into each other’s way.

Will the budget provide the push to get us to the upper right hand corner? Only time will tell.

Sources:

- Issues in the Coordination of Monetary and Fiscal Policy (pdf)

- Early 1980s recession (Wikipedia)

- Against the Gods: The Remarkable Story of Risk (Amazon)

![]() , we saw how the ideal relationship between the central bank and the government is one where neither party gets what it wants, but there’s a stable outcome. Here are a bunch of articles that expands on the conundrum faced by a central bank.

, we saw how the ideal relationship between the central bank and the government is one where neither party gets what it wants, but there’s a stable outcome. Here are a bunch of articles that expands on the conundrum faced by a central bank.