Traffic jams

Say there’s a traffic jam on a busy road. When new vehicles try to enter the same route, the drivers hear on the radio that there’s a jam ahead and adapt by finding another route. Suppose there is only one alternate route. What happens now? The alternate route forms a second jam!

Later entrants have to choose between the two jams. Predicting the actions of this new group is very hard to do. Maybe the second jam is worse than the first. By the time we hit this third layer of participants, predicting the behavior of the system has become extremely difficult, if not impossible.

Complex vs. Complex Adaptive

Weather is a complex system. However, if, on Thursday, the forecast is for rain on Sunday, is the rain any less likely to occur? No. The act of predicting has not influenced the outcome. Although near-term weather is extremely complex, with many interacting parts leading to higher order outcomes, it does have an element of predictability.

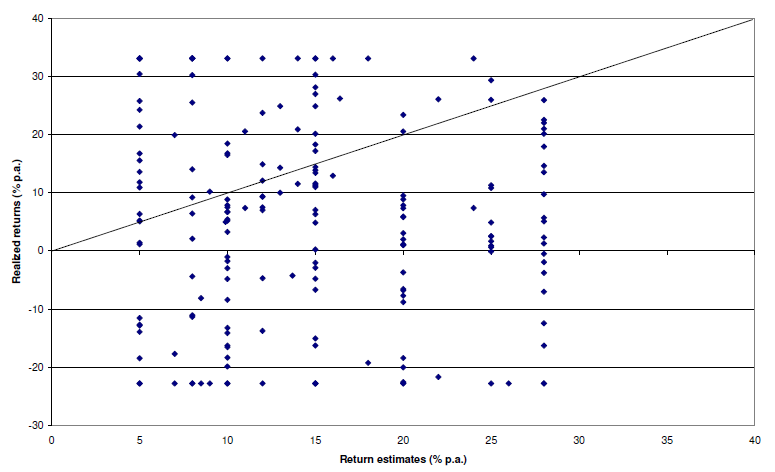

The stock-market is a complex adaptive system. Traders and investors in the market are interacting with one another constantly and adapting their behavior to what they know about others’ behavior. The key element of a complex adaptive system is the social element.

For example, Meredith Whitney predicted the crash of Citibank in late 2007.

She went on to setup her own advisory firm, Meredith Whitney Advisory Group, and made a similar call on American municipal bonds in late 2010 on national television. Retail investors sold in panic. But for the the most parts, nothing happened.

Reflexivity

Reflexivity refers to circular relationships between cause and effect. A reflexive relationship is bidirectional with both the cause and the effect affecting one another in a situation that does not render both functions causes and effects. It flies in the face of equilibrium theory, which stipulates that markets move towards equilibrium and that non-equilibrium fluctuations are merely random noise that will soon be corrected.

Reflexivity asserts that prices do in fact influence the fundamentals and that these newly-influenced set of fundamentals then proceed to change expectations, thus influencing prices; the process continues in a self-reinforcing pattern.

Takeaway

Behavioral dynamics is key to understanding complex adaptive systems. One should have a mental model that incorporates higher-order thinking when it comes to navigating the markets.

The big question is, how different is listening to stock-market predictions from listening to an astrologer, reading horoscopes or believing in vastu?

To quote German theologian and martyr Dietrich Bonhoeffer:

“…how wrong it is to use God as a stop-gap for the incompleteness of our knowledge. If in fact the frontiers of knowledge are being pushed further and further back (and that is bound to be the case), then God is being pushed back with them, and is therefore continually in retreat. We are to find God in what we know, not in what we don’t know.”

Sources

Related articles